Colombia: Human rights defenders continue to face pressure and attacks

A special feature by Juan Velez Rojas

For several decades, Colombia has been a dangerous country for human rights defenders (HRDs) to carry out their critical work. Despite government measures to protect them and the signing of the 2016 Peace Agreement, this situation has not changed and may even be getting worse.

Venezuela: indigenous peoples face deteriorating human rights situation due to mining, violence and COVID-19 pandemic

Venezuela is suffering from an unprecedented human rights and humanitarian crisis that has deepened due to the dereliction by the authoritarian government and the breakdown of the rule of law in the country.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has estimated that some 5.2 million Venezuelans have left the country, most arriving as refugees and migrants in neighbouring countries.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in 2018 had categorized this situation of human rights, as “a downward spiral with no end in sight”.

The situation of the right to health in Venezuela and its public health system showed structural problems before the pandemic and was described as a “dramatic health crisis (…) consequence of the collapse of the Venezuelan health care system” by the High Commissioner.

Recently, the OHCHR submitted a report to the Human Rights Council, in which it addressed, among other things the attacks on indigenous peoples’ rights in the Arco Minero del Orinoco (Orinoco’s Mining Arc or AMO).

Indigenous peoples’ rights and the AMO mining projects before the covid-19 pandemic

Indigenous peoples have been traditionally forgotten by government authorities in Venezuela and condemned to live in poverty. During the humanitarian crisis, they have suffered further abuses due to the mining activity and the violence occurring in their territories.

In 2016, the Venezuelan government created the Orinoco’s Mining Arc National Strategic Development Zone through presidential Decree No. 2248, as a mega-mining project focused mainly in gold extraction in an area of 111.843,70 square kilometres.

It is located at the south of the Orinoco river in the Amazonian territories of Venezuela and covers three states: Amazonas, Bolívar and Delta Amacuro.

It is the habitat for several indigenous ethnic groups[1] who were not properly consulted before the implementation of the project.

The right to land of indigenous peoples is recognized in the Venezuelan Constitution. Yet, as reported by local NGO Programa Venezolano de Educación- Acción en Derechos Humanos (PROVEA), the authorities have shown no progress in the demarcation and protection of indigenous territories since 2016.

Several indigenous organizations and other social movements have expressed concern and rejected the AMO project.

The implementation of this project has negatively impacted indigenous peoples’ rights to life, health and a safe, healthy and sustainable environment. Human Rights Watch, Business and Human Rights Resource Center, local NGO’s, social movements and the OHCHR, have documented the destruction of the land and the contamination of rivers due to the deforestation and mining activity, which is also contributing to the growth of Malaria and other diseases.

Indigenous women and children are among the most affected. The Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) has reported that “the indigenous populations living in border areas of Venezuela are highly vulnerable to epidemic-prone diseases”, and it raised a special concern about the Warao people (Venezuela and Guyana border) and Yanomami people (Venezuela and Brazil border).

Women and children also face higher risks of sexual and labour exploitation and of gender-based violence in the context of mining activities.

The High Commissioner’s recent report mentions that there is “a sharp increase since 2016 in prostitution, sexual exploitation and trafficking in mining areas, including of adolescent girls.”

In addition, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have identified a trend among adolescents of dropping out of school particularly between the ages of 13 and 17. Indigenous individuals are acutely affected, as many children leave to become workers at the mines.

Violence and crime have also increased in the AMO. Criminal organizations and guerrilla and paramilitary groups are present in the zone, and the Venezuelan government has expanded its military presence. Indigenous leaders and human rights defenders have been targets of attacks and threats; and there is a persistence of allegations of cases of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial and arbitrary killings.

Current situation under COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of adequate response to it has aggravated this situation.

The government declared a state of emergency (estado de alarma) on 13 March and established a mandatory lockdown and social distancing measures. Yet mining activities have continued without adequate sanitary protocols to prevent the spread of the pandemic.

The State of Bolívar -the largest state of the country which is located in the Orinoco Mining Arc- has among the highest numbers of confirmed cases of COVID-19 which have included indigenous peoples.

The Venezuelan authorities’ response to the pandemic in these territories has not considered culturally appropriate measures for them. In addition, although authorities established a group of hospitals and medical facilities called “sentinel centres” to attend persons with COVID-19 symptoms, they are located in cities while indigenous communities live far from cities.

Furthermore, the lack of petrol in the country aggravates the obstacles to easy transportation to these centres.

Civil society organizations and indigenous leaders complain about the lack of COVID-19 tests and the data manipulation of the real situation of the pandemic. Also, the OHCHR reported the arbitrary arrest of at least three health professionals for denouncing the lack of basic equipment and for providing information about the situation of COVID-19, and stressed that there are “restrictions to civic and democratic space, including under the “state of alarm” decreed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

[1] At least Kari’ña, Warao, Arawak, Pemón, Ye’kwana, Sanemá o Hotï, Eñe’pa, Panare, Wánai, Mapoyo, Piaroa and Hiwi.

Download

Venezuela-COVID19 indigenous-News Feature articles-2020-ENG (full article with additional information, in PDF)

Latin American judges address challenges and opportunities in addressing human rights impact of businesses

Judges from six Latin American countries revealed that there were serious obstacles, but also possibilities for justice, facing regional judiciaries as they try to protect the human rights of those who have been adversely affected by the activity of business entities.

The judges gathered as part of the Regional Judicial Dialogue on Business and Human Rights organized by the ICJ of Jurists on September 7.

The Dialogue, moderated by ICJ Commissioner Professor Monica Pinto, brought together 17 judges from Central and South America to consider the role of judges in guaranteeing the right of access to justice and remedy and reparation. The judges also considered the need to guarantee the independence of the judiciary and the security of individual judges, lawyers, and human rights defenders in the context of business activities in the region.

The session featured presentations from a member of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. The Dialogue took place in the context of the 5th Regional Forum on Business and Human Rights for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Discussing access to justice and remedy and reparation, the judges shared experiences and jurisprudence in cases related to serious crimes, including against humanity committed during the Argentine military regime, as well as cases of serious corruption and embezzlement in Guatemala.

In Argentina, in a case concerning the 1976 kidnapping and torture of 24 workers employed by the local Ford Motor company at their factory in Buenos Aires during the 1976-83 military dictatorship, a Federal Trial Tribunal sentenced three persons, a former military officer and two former Ford executives to prison of between 10 and 12 years, for their complicit involvement in the crimes.

Former Ford executives were accused of providing detailed information and logistical support to security agents that led to the abduction and torture of the victims, and also allowed a detention centre to be set up inside the premises of that factory.

The three judges of the Tribunal in this case attended the meeting to share the lessons learned and the significance of the criminal proceedings in the context of efforts to bring justice and reparations for the crimes of the past.

The process and the final sentence is a landmark in the fight against impunity in Argentina and an important message to all so that these crimes are not committed again. The case clarified the ways in which private individuals (the former company executives) participated in the commission of the crimes by State agents (military and security agents), elaborating upon modalities of attribution of the acts to the accessory perpetrators.

It is also an innovation in the ways it gathered and assessed the probatory value of the available evidence of crimes committed more than 30 years ago so that the crimes could still be attributed to the perpetrators.

The reparation ordered by the Tribunal in this case was “symbolic and historical”, consisting on an acknowledgment of the facts by the State and the private actors. The victims may demand now other forms of reparation from the State, but not from individuals.

The company as such was not part of the criminal proceedings nor was it sanctioned in the final sentence, since Argentinian law does not accept the criminal responsibility of legal entities such as corporations.

A participant judge from Guatemala shared a case concerning economic crimes of corruption, fraud, illicit association and assets laundering in a provincial town in Guatemala. Here, the experience and outcomes were somewhat different.

The case involved the town major and several of his relatives as well as some 20 companies out of which nearly 20 individuals and seven companies received penalties in the final sentence.

The case is of special significance in Guatemala as one of the few, large scale, corruption cases that has reached its final stage with convictions. In the investigation and collection of evidence considered during the trial, participated several public offices and the then International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), which is no longer in operation.

Thanks to recent laws on corruption and money laundering, it is possible to impose sanctions on the company, as a legal entity. In the instant case, those sanctions consisted of monetary fines but not suspension or dissolution of the legal entity to allow other administrative proceedings against the same companies to continue.

In accordance with national laws and international standards, the judges ordered full reparation, including for damages, measures of satisfaction such as public statements of apologies and publications to be made by the convicted.

Citing a graphic statement contained in the final sentence, the judge Pablo Xitumul who presided the Tribunal said “corruption and impunity are even more lethal than a cancer or a pandemic, and should be combated without delay or excuses!”

Read the full story here: Americas-Judges and BHR-News-Feature article-2020-ENG

COVID-19: ICJ calls on African States to protect women from escalating sexual and gender based violence

While reports suggest a decrease in crime during lockdown due to restricted movement, violence against women, including gender-based violence (GBV), continues unabated, and has likely worsened throughout Africa, replicating global trends in this regard.

Africa has a serious GBV crisis, which domestic legislative frameworks and accountability mechanisms have failed to fully address.

Various factors contribute to the increasing incidence of GBV in Africa. These factors are facilitated by the failure of States to adequately discharge their obligations to protect persons from gender based violence, through legal reform and administrative actions.

The issues manifest in gender insensitive actors and institutions that administer justice, impunity for abuses, and limited capacity of justice actors to properly handle cases due to lack of training and resources.

There are also challenges in issuance of restraining and protection orders. All these problems are reinforced by a widespread lack of willingness to recognize, understand and engage with women’s rights by State actors.

In Africa, more than one in three women (36.6%) report having experienced physical, and/or sexual partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner. Studies have also found that the highest prevalence of child sexual abuse is in Africa.

This GBV crisis in Africa has been worsened by the coronavirus pandemic, which has contributed to a surge in GBV. The pattern of rape, sexual violence, and killing of women continues to spread across the continent, even during this health crisis.

On 27 May, the news of the rape and killing of a 22-year-old student while she studied in an empty church in Nigeria sparked outrage and protests in many parts of the country.

In South Africa, the body of 28-year-old woman Tshegofatso Pule was found on 8 June. She had been stabbed and hanging from a tree; she was eight-months pregnant at the time.

There have been several reports of femicide since some COVID-19 restrictions were lifted in South Africa. In Zimbabwe, increasingly there have been reports of rape and other sexual violence being used as political weapons to suppress political opposition in Zimbabwe.

Recently, there have been reports that three leaders of the MDC-A party were abducted and subjected to torture which included sexual violence after staging a flash demonstration against failure of the government to address livelihood issues during the Covid-19 lockdown.

While the demonstrations were led by both men and women, allegations focused on sexual violence against women by State agents have been made on numerous occasion especially following protests against the government. In both instances the response by the State authorities has been to challenge the allegations before conducting a thorough investigation.

In the recent case of the MDC-A leaders, officials have not only refuted the allegations but also charged the victims for breaching Covid-19 regulations and recently arrested them for allegedly ‘faking abduction’ and lying about torture..

Global Standards

All States must protect against gender based violence, whether by State or private actors, pursuant to their obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the UN Convention Against Torture, the Convention on the Prevention of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Most African countries are parties to these international treaties.

In addition, States of the African Union are bound to respect a range of international law and standards which prohibit gender based discrimination and sexual violence, most notable are the African Charter, and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women (the Maputo Protocol) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.

Article 4 of the Maputo Protocol provides that “every woman shall be entitled to respect for her life and the integrity and security of her person. All forms of exploitation, cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment and treatment shall be prohibited.

States parties shall take appropriate and effective measures to enact and enforce laws to prohibit all forms of violence against women, including unwanted or forced sex whether the violence takes place in private or in public.” Article 16 of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child includes sexual abuse of children as a form of torture, cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment.

As explained by the CEDAW Committee, all States, including African States, have a due diligence obligation to prevent, investigate, prosecute and punish rape and other GBV.

It is noteworthy that, 17 years into its existence, not all African countries have ratified or signed the Maputo Protocol, with only 42 out of 55 AU member states having ratified the convention. Of the few countries which have comprehensive domestic legal frameworks to eliminate all forms of violence against women, they too often face challenges in implementation.

States have the primary responsibility to take effective measures to eradicate GBV. States have an obligation to take the necessary action at all levels to ensure the elimination of harmful gender norms and stereotypes, as well as to ensure the elimination of GBV.

African countries need to urgently respond to the scourge of GBV in the region. The ICJ intends to publish a series of legal briefs on the “State of Rape Law” as provided in various jurisdictions in Africa, in order to highlight the challenges in criminal justice systems in relation to addressing the crime of rape and to provide concrete recommendations for reform.

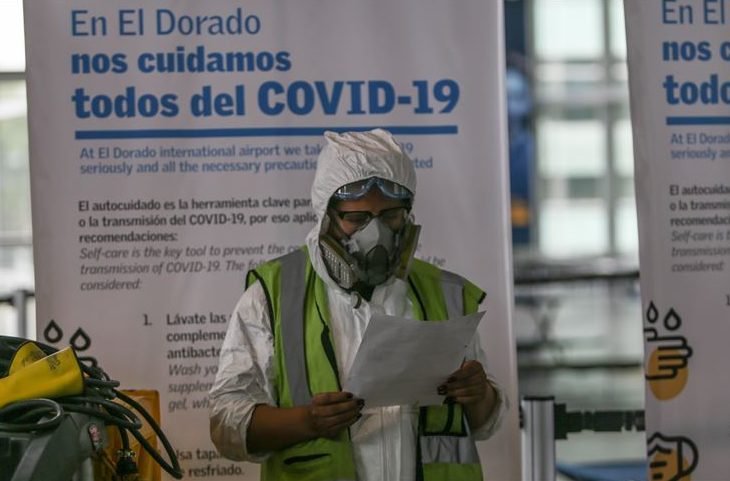

Colombia: COVID-19 policies should include conflict-related measures, especially for human rights defenders

A Feature Article by Rocio Quintero, Legal Adviser, ICJ Latin American Programme, based in Bogota.

Throughout several decades, a large number of Colombians have been victims of serious crimes related to the ongoing armed conflict. In particular, human rights defenders have been targets of serious human rights violations and abuses, such as killings, death threats, and harassments.

Just this year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has received information of 56 possible cases of killings of human rights defenders. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 outbreak has not stopped the violence against human rights defenders.

In that regard, since the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the country on 6 March 2020, the Organization of American States (OAS) and International Amnesty has reported six killings. The perpetrators of those crimes have not been identified yet.

Human rights violations and abuses against local communities have not stopped either. Quite the opposite seems to be true.

In that regard, it is said that armed groups, including paramilitary groups and new groups made up of dissident FARC-EP members, are taking advantage of the outbreak to commit illegal actions with fewer constraints, mainly, in rural areas of the country.

Among these actions, it should be highlighted the enforced displacement of 250 people and the forced confinement of 770 families due to combats between a paramilitary group and a guerrilla group. Both actions took place in the pacific region of the country, an area where the conflict has intensified after the peace agreement. In addition, at least three ex-members of the FARC-EP have been murdered in March 2020.

Despite the seriousness of the situation described above, the Colombian government response to the COVID-19 crisis has focused on the creation and implementation of non-conflict-related measures.

In that regard, the Government has decreed various and vital regulations to mitigate the social and economic impact created by the virus. Among others, the president declared a state of emergency and a mandatory 19-day national quarantine that started on 25 March 2020.

The Government also established a program of economic and social aid for those who will be affected most by the quarantine.

None of the measures were designed bearing in mind the particular situation of human rights defenders. Consequently, their protection is not a central element of the Colombian pandemic policies.

Since the implementation of the peace agreement and victims’ rights are not top priorities of the current Government, the approach adopted is not entirely unexpected.

Although, to be fair, it should be recognized that the State programmes for the implementation of the peace agreement have continued operating during the pandemic.

It might be argued that the pandemic has the potential to affect predominantly human rights that have not been directly linked with the internal conflict.

Therefore, following this point of view, the prioritization of non-conflict-related measures is justified and required.

Although this position is based on a valid premise, which is that the COVID-19 pandemic creates several challenges that go beyond conflict-related human rights problems, it ignores a central element of Colombian reality: the existence of an ongoing armed conflict.

Currently, the conflict affects a considerable part of the Colombian population directly, including the majority of human rights defenders. In that regard, last year, it was reported illegal actions related to the internal armed conflict in at least 10 out of 32 departments of Colombia.

In this context, ignoring the importance of the conflict might lead to the implementation of ineffective pandemic measures. This is because, in conflict zones, the protection of human rights requires addressing the specific challenges that the pandemic has created in those territories.

For instance, the presence of illegal groups can prevent local communities from getting tested for COVID-19 and access to health services. Likewise, due to the quarantine, illegal groups might identify easier the location of human rights defenders and retaliate against them.

In relation to human rights defenders, it should also be highlighted the problems related to access to adequate protection measures. In that regard, Amnesty International has denounced that the protection measures for some human rights defenders have been reduced due to the pandemic.

In a similar way, a local NGO expressed concerns for the decision of the National Protection Unit to suspend indefinitely the sessions of the commission where protection measures are defined.

In light of the above, beyond political considerations and the general Government’s priorities, it is imperative that the Government adopts a more comprehensive approach to tackle the pandemic.

It should address the differential impact the pandemic might have on people who lead social and legal transformations in the conflict zones of the country.

In particular, it should implement or adapt protection measures to be effective during the COVID-19 crisis. Similarly, the right to an effective remedy and reparation should also be not only guaranteed, but realized, in compliance with international standards.

Additionally, it is also important that the national Government reinforce its efforts to obtain a humanitarian ceasefire by all illegal groups during the COVID-19 crisis.

A total ceasefire would contribute to (i) protecting the civilian population for violent actions, (ii) implementing the pandemic measures in conflict zones, and (iii) avoiding a proliferation of the virus in vulnerable communities.

This is a crucial measure that has already been requested by national civil organisations, the Head of the UN Verification Mission in Colombia, the OAS, and some parliamentarians.

As yet, only one illegal group has accepted a ceasefire: the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), the largest active guerrilla in Colombia, who declared a unilateral ceasefire during April.

To conclude, acknowledging the importance of the conflict is essential to tackle the human rights implications of the COVID-19 crisis.

This is not only necessary to have comprehensive pandemic policies, but also to make sure that the problems and needs in the conflict zones are not neglected and aggravated during the pandemic.

On this point, as recently stated by UN Secretary-General, people who are most vulnerable during a conflict are also “most at risk of suffering “devastating losses” from the disease.”