Apr 2, 2020 | News, Op-eds

An opinion piece by Shaazia Ebrahim, ICJ Media Officer, and Tim Fish Hodgson, ICJ Legal Adviser on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, based in South Africa.

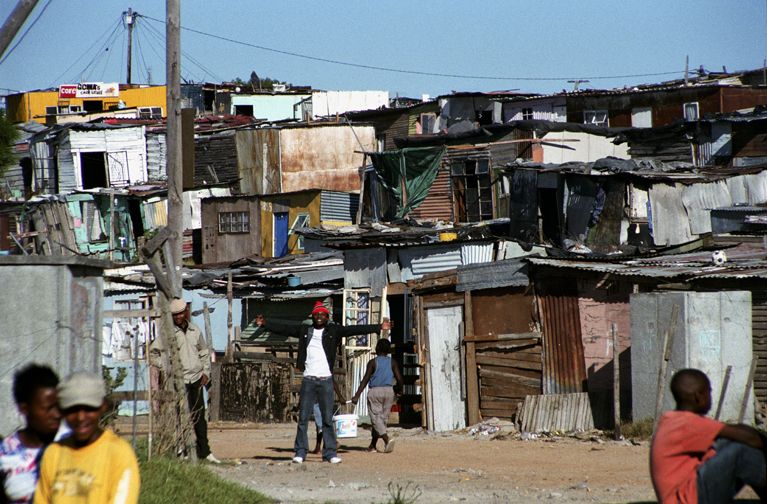

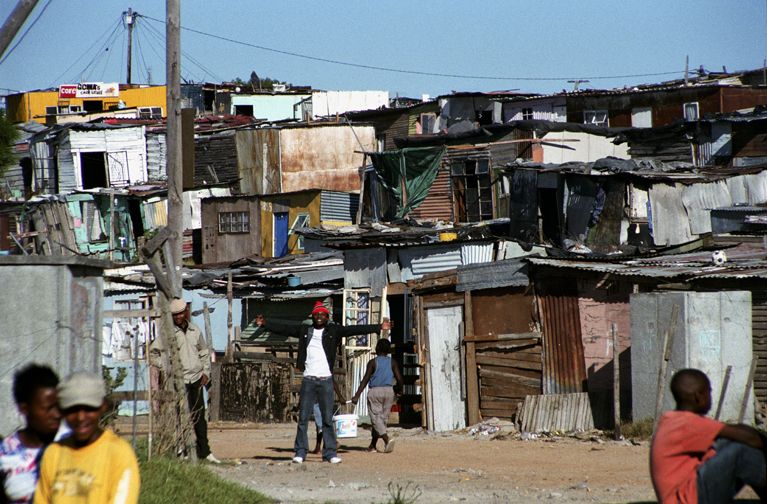

The inhumane conditions that most South African residents are subjected to in their daily lives will continue to deepen as the coronavirus spreads.

South Africans are encouraged to take precautionary measures to curb the spread of the pandemic by practising social distancing and intensifying hygiene control. The country will also be under a nationwide lockdown in order to “fundamentally disrupt the chain of transmission across society” from 26 March for 21 days.

The problem is that the recommended measures in South Africa, similarly to those of the World Health Organisation, assume that everyone lives in a house. A house which is at no risk of being destroyed by the state or private owners of the land upon which it is built: a house with access to water, sanitation and other basic services.

But the reality is that millions of South Africans do not live in a house, but in rudimentary structures in poor conditions. In a statement released this week, Abahlali baseMjondolo, a shack dwellers’ movement with members in various provinces across South Africa, articulated this.

Abahali’s frank assessment of the situation is that “it does not seem possible to prevent this virus from spreading when we still live in the mud like pigs”.

It is under the same conditions described by Abahlali baseMjondolo that many of the urban and rural poor in South Africa will be required to live under “lockdown”, commencing from midnight tonight.

Access to basic services: ‘if one person gets infected it’s disastrous’

Speaking before the release of the statement, Abahlali president S’bu Zikode expressed the distress that many around South Africa are currently experiencing. “Abahlali is very concerned about the outbreak of the coronavirus. The reason is, of course, that the conditions that we are subjected [give] us reason to be scared and worried,” he said.

“Social distancing” is difficult for many in South Africa. Government regulations say no more than 100 people should be “gathering” and people are more generally encouraged to keep a distance from one another. In Abahlali’s settlements, Zikode explains, there are thousands living close together under strenuous conditions.

“That on its own is automatically disrespecting the call from the president”, he said.

Abahlali, alongside various other South African movements and organisations, have for years been calling for the state to improve their living conditions and provide them with access to water, sanitation and other basic services.

In 2019 the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights noted its concern about “the large number of people living in inadequate housing, including those in informal settlements, without access to basic services; the growing number of informal settlements in urban areas due to rapid urbanisation”.

These calls have not received a sufficiently serious response from the government. Litigation to ensure access to basic services remains commonplace.

In this context, while hygiene has rightly been touted as one of the most important preventatives from spreading Covid-19, it is difficult to imagine how the majority living in South Africa will be able to ensure even basic measures such as handwashing.

Abahlali notes that in many informal settlements “hundreds of people [are] sharing one tap”. In this context, it is easy to see why leaders of Abahlali think that as it stands, preventing the spread of coronavirus is very important, but all but impossible.

“As leaders of Abahlali, we see it as once one person gets infected in the settlements, suddenly the entire settlement will be disastrous,” Zikode said.

A moratorium on evictions: halting evictions ‘will save lives’

Making matters worse, members of Abahlali, like many others in their country, lack security of tenure. As trying as their current circumstances may be, Abahlali warns of the potentially devastating effects of evictions during the pandemic. Another common way to induce evictions is to disconnect existing access to water, electricity and sanitation.

This is why Abahlali demands that “all evictions must be stopped with immediate effect” and that “all disconnections from self-organised access to water, electricity and sanitation must be stopped with immediate effect”. Indeed, it is difficult to see how any eviction during the pandemic could be “just and equitable” in “all relevant circumstances” as is required by South African law.

The call for a “moratorium” on evictions has also been made by a large group of social movements and civil society organisations in South Africa in a letter to the president. It has also received clear support from the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, who has called for a “global ban” on evictions worldwide:

“The logical extension of a logical stay-at-home policy is a global ban on evictions. There must be no evictions of anyone, anywhere, for any reason. Simply put: a global ban on evictions will save lives”, she said. The International Commission of Jurists has echoed these calls and the calls for connection of emergency water for all before the nationwide lockdown commences.

Coronavirus, the right to housing and access to land

In February, in giving input to the parliamentary committee contemplating the need to amend the Constitution to expedite land reform, Abahali argued that land is not a commodity and that the Constitution should include a “right to land” which it does not at present.

“Land should be shared and should be viewed as a public good”, Zikode explains.

Abahlali argues that the absence of a right to land in the Constitution undermines the constitutional right to housing: without land there can be no housing. Consistently with this logic, as early as 2000, South Africa’s Constitutional Court held emphatically that:

“For a person to have access to adequate housing all of these conditions need to be met: there must be land, there must be services, there must be a dwelling.”

The current crisis brought on by the coronavirus adds weight to Abahlali’s position on land. Access to land and security of tenure are necessary for access to adequate housing. If people have access to land and secure tenure, evictions are not a constant threat to their well-being.

Without access to housing and basic services, public health is severely compromised on a daily basis. Public health emergencies such as the coronavirus pandemic put even further pressure on an already compromised living environment. They therefore highlight that for many people, the right to adequate housing can only be discharged with full access to land.

The obligations of the South African government

The government of South Africa has rightly been praised for its proactive response to the coronavirus pandemic. The regulations passed in terms of the Disaster Management Act require that measures taken to combat coronavirus are implemented “as far as possible, without affecting service delivery in relation to the realisation of the rights” including the rights to housing and basic services, healthcare, social security and education.

The president’s announcement of a countrywide lockdown included a commitment that “temporary shelters that meet the necessary hygiene standards will be identified for homeless people”. Nevertheless, Abahlali’s members, who are not strictly homeless, might take cold comfort.

Disappointingly, the president failed to announce a moratorium on evictions or make any mention of evictions at all. This not only leaves many more people under the threat of being rendered homeless but may also lead to devastating displacement that will make the further spread of coronavirus possible.

The president did indicate that “emergency water supplies” are “being provided to informal settlements and rural areas”.

However, he did not make mention of whether expedited or emergency provision of other basic services such as sanitation, electricity and waste removal services where they are not currently available would occur. Urgent calls for emergency water connection coming out of Khayelitsha suggest that in many places in major informal settlements such emergency connections have not occurred.

The government of South Africa should be applauded for taking emergency measures. However, in so doing, it is implicitly acknowledging that many — if not most — South African residents have been living on a daily basis in conditions that are insufficient for them to live healthy, dignified lives.

This highlights the government’s existing and continuous failures to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights to access to housing and basic services.

The coronavirus, therefore, stands a stark reminder to all in South Africa of the dire impacts of social inequality in the country and the pressing need for government to pursue the realisation of all its obligations in terms of social and economic rights protected in the South African Constitution and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It also lends strong credence to the need for serious consideration of Abahlali’s claim for the need of a constitutionally protected right to land.

As Zikode concludes:

“Abahlali has always been about the land, decent housing, and dignity. Without land, housing is impossible. Without land, dignity is compromised. Land is close to the heart of many mainly black South Africans and it’s very close to the heart of Abahlali.”

Originally published in Daily Maverick

Nov 1, 2019 | News, Op-eds

An opinion editorial by Shaazia Ebrahim, Communications Consultant for ICJ’s Africa Programme.

Nomfundo Ngobese (25) was used to waking up at 4am to walk the 35km from her home in Nquthu, northern KwaZulu Natal (KZN) to school. In the blistering heat and the freezing cold, crossing rivers and sometimes dodging rain and lightning, Ngobese, was like many South African school learners who walked for hours to get to and from school each day.

“We had to wake up past 4 so that at past 5 we can go to school. In winters when we had to go to school, it was dark. We didn’t feel safe… We didn’t even realise the difficulties our smaller siblings were facing. It’s a thing that we just got used to,” Ngobese said.

While learners all over South Africa walk for hours every day to get to school and back home, KZN has the greatest need for scholar transport. According to the 2016 General Household Survey done by Statistics South Africa, some 483 633 learners in KZN walk more than half an hour in one direction to school each day.

But the end of the battle for learners with similar experiences to Ngobese could be in sight.

On October 23, Ngobese joined other Equal Education (EE) post-school youth organisers in picketing outside the Pietermaritzburg High Court. EE, represented by the Equal Education Law Centre (EELC), had sued the KZN Department of Education (DoE) to court to force the government into releasing the provincial scholar transport policy, which should have been available in December 2018.

They emerged victorious when government committed to releasing its Scholar Transport Policy for public comment by 31 January next year. Should the KZN DoE fail to comply, it will have to answer to the courts. The release of this policy is a critical step in ensuring that more learners will be able to have access to school transportation.

EE has been working to achieve free and safe scholar transport in Nquthu since 2014, after Equalisers told EE about the difficulties they faced with scholar transport. Learners highlighted the challenges they faced walking very far distances in extreme heat and in thunderstorms, and crossing rivers and mountains, at great risk of violent crime including sexual assault. Many learners said they felt tired and hungry after the long walk, and could not concentrate properly in class or perform well at school.

“I was once an Equaliser myself and I once walked to school every morning and afternoon,” Palisa Motloung (21) said. “We were never sure what’s going to happen on those routes. I remember this one time when I was walking with my friend, and then we passed a bush and there were men there talking. We couldn’t tell if they were talking on this side or that side of the fence because it was dark. It was very scary, we literally had to run. It was quite an experience and I don’t wish any child should go through that,” Motloung said.

After local visits to schools in Nquthu in 2014 and 2015, EE wrote to the KZN Department of Transport (DoT) and KZN DoE about these hardships learners were facing, and requested information about how they were providing scholar transport in the province. Governments’ replies were unsatisfactory, with the DoE responding that it found that only one of the 12 schools EE discussed qualified for scholar transport.

After long back and forth with government, who provided scholar transport in dribs and drabs, EE found that there was still a desperate need for scholar transport. Government officials claimed that five of the 12 schools did not qualify for scholar transport because learners were not attending the schools closest to their homes. They conceded that seven of the 12 schools did qualify for scholar transport, but said there was no money to provide it. EE took the matter to court.

This is not the first time that a provincial department of education has sued in South Africa for a failure to provide transport for learners. In 2015 the Judge Plasket of the Eastern Cape High Court held in a similar case that “The right to education is meaningless without … transport to and from school at state expense”.

The initial case was set to be heard at the Pietermaritzburg High Court. But before the hearing began, the lawyers representing EE and the lawyers representing the KZN government entered into negotiations with the KZN DoE and KZN DoT made certain promises. The order granted by the Pietermaritzburg High Court stated that the KZN DoE promised to provide scholar transport to learners in the 12 Nquthu schools by 1 April 2018.

While this was a momentous victory for EE, as part of ongoing court processes, the organisation filed a response to the KZN DoE report to the court, recognising the important steps that it had taken, but also noting significant gaps that remain.

The EE urged the KZN DoE in June last year to provide clear timelines for the finalisation of its scholar transport policy. This is a crucial step to clarify which learners qualify for government-subsidised scholar transport, how the KZN DoE and the KZN DoT will work together to provide scholar transport, and how learners’ safety will be ensured.

This report has been delayed for over a year now, but if the decision of the Court is to be implemented, it will be released in January next year.

After coaxing from South African civil society, including EE, The National Learner Transport Policy was finally published in October 2015. The policy contains important scholar transport guidelines and principles that provinces should adhere to. However, while this policy has been finalised, it has yet to be adopted.

The government’s failure to provide learners with transport is a violation of the right to basic education which is protected under the South African Constitution and international law. The International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, which South Africa ratified makes clear that education must be free for all learners at a primary school level and should progressively be made free for all learners at all levels.

Free education includes not only the absence of fees but also all other costs include free, reliable and safe transport. This means learners have a right to access their schools safely, and on time, so that they can use their energy to concentrate in class. For many learners in South Africa this is impossible without government funded transport.

“Most of the time, [schoolchildren] wake up very early and they get to school very hungry and tired. This affects their school percentage, the pass rate of the school also gets affected because of the long kilometers that children have to walk to school,” Sanele Zulu (22) said.

“I walked to school but I didn’t even know it was a wrong thing to do until Equal Education came and opened our minds. Even our parents didn’t know it was wrong, they thought that because in the olden days they walked long distances, so we must get used to it. But when EE came to our rural village, something went off in our eyes and we saw things in a different way,” Ngobese said.

Reflecting on their own experiences during school Ngobese, Motloung, and Zulu, continue to use their voices for learners who walk long distances to go to school. Equal Education, with the legal assistance of EELC, continues to advocate for the rights of learners in KwaZulu-Natal and all over South Africa.

Even though the persistent delays in the development and implementation of government policies to facilitate free, safe transport to and from schools is a cause for concern, learner’s faith in the judicial system and rights-based advocacy should be a source of optimism about the future of constitutional democracy in South Africa.

This op-ed was originally published in the Mail & Guardian.

Jul 19, 2019 | News, Op-eds

An opinion piece by Emerlynne Gil, Senior Legal Adviser, ICJ Asia-Pacific Programme.

Last week, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution expressing concern over the human rights situation in the Philippines. It specifically expressed grave concern over the killings and disappearances arising from the drug war of the current administration.

Since 2016, when the government began its campaign against illegal drugs, there have been reports of thousands of killings of people who were allegedly involved in the drug trade and drug use.

Furthermore, in the recent report of Lawyers Rights Watch Canada (LRWC), there have been more than 40 lawyers killed under the current administration.

The resolution was, in fact, restrained in tone and content. Human rights groups like the ICJ had hoped that it would establish an international mechanism to investigate the killings and other human rights violations.

However, the Council held back and merely urged the Philippine government to “take all necessary measures to prevent extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances”.

It also asked the Philippine government “to cooperate with the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights” and other international human rights mechanisms, and requested the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to present a report to the Council for discussion in June 2020.

The Philippine government sent a big delegation to Geneva to lobby against the adoption of any resolution. During the informal consultations among States on this resolution, there were theatrics from the delegation, which walked out during the first consultation.

At the second consultation, nobody from the delegation attended, but former Ambassador Rosario Manalo, who also previously represented the Philippines in the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR), and is now a member of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, was present.

Purporting to speak as a ‘human rights defender’, she launched an angry tirade against Iceland as the sponsor of the resolution and the other States who supported it.

She also called the Filipino human rights defenders in the room who were seated right next to her as ‘treacherous’, and accused them of peddling lies about the country.

The theatrics in Geneva did not serve the Philippine government well. In the end, the Council voted to adopt the resolution.

Now that it has been adopted, what does this mean for Filipinos? The UN Human Rights Council, like any international human rights body, has significantly limited ability to directly protect human rights on the ground.

Thus, while it has adopted this resolution, the Council will not have the power to actually stop the unlawful killings and other human rights violations being committed. The Council will be unable to compel the implementation of the recommendations in any resolution it adopts, where a State is unwilling to cooperate.

Hence, the Philippine government still holds the discretion on whether or not to implement the recommendations made by the Council.

This is where ordinary Filipinos come in. The people – as the eyes and ears on the ground – are indispensable to the work of international human rights bodies like the Human Rights Council.

The effectiveness of the Council in protecting human rights on the ground greatly relies upon the extent to which the people on the ground – including human rights defenders – are able to engage and work with them.

The information provided by the general public regarding the situation on the ground is very important to the work of international human rights mechanisms like the Council. This information gives these mechanisms a clearer and more accurate picture of the human rights situation in the country.

We should thus not be silent. We should continue pressing the government to implement the recommendations in this resolution. The key recommendation is that the government should investigate extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances and hold the perpetrators accountable.

In its formal statement to the Council after adoption of the resolution a few days ago, the representative of the Philippine government at the Council vigorously claimed that the country has ‘fully functioning domestic accountability mechanisms’, ignoring the fact that authorities have been unwilling or unable to conduct effective investigation or prosecutions for any of the numerous allegations of unlawful killings.

Hence, we should press the government to demonstrate that its claim that domestic accountability mechanisms are functioning is true, and that it should then use these mechanisms by investigating the killings and disappearances and punishing the perpetrators.

It is a welcome development that the Human Rights Council passed this resolution on the human rights situation in the Philippines.

But the work does not end there. There is a symbiotic relationship between the actions of the people on the ground and the work of international human rights mechanisms like the Council.

It is now left to us to press our government for the implementation of the recommendations in the resolution.

Jul 26, 2018 | News, Op-eds

An opinion piece by Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser in Bangkok, Thailand.

Over recent decades, international observers have tended to view the human rights and political situation in Cambodia as a series of predictable cycles that does not warrant too much alarm.

The conventional wisdom has been that Prime Minister Hun Sen and his government routinely tightens their grip on the political opposition and civil society in advance of elections before relaxing it again after victory has been secured.

But that analysis is no longer valid.

The reason is simple: During the course of ensuring it will win the national election scheduled for this Sunday (29 July), Hun Sen’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has, since the last election, systematically altered the country’s constitutional and legal framework – and these changes will remain in place after the election has passed.

Through the passage of a slew of new laws and legal amendments inconsistent with Cambodia’s obligations under international law, and the frequent implementation of the law to violate human rights, the legal system has been weaponized to overwhelm and defeat the real and perceived opponents of the CPP, including the political opposition, the media, civil society, human rights defenders and ordinary citizens.

This misuse of the law is a significant development in the history of modern Cambodia and represents a determined move away from the vision enshrined in the historic 1991 Paris Peace Agreements that ended years of conflict and sought to establish a peaceful and democratic Cambodia founded on respect for human rights and the rule of law.

And it risks cementing the human rights and rule of law crisis that now exists within Cambodia for years to come.

To facilitate the closure of civil society space, and contrary to international law and standards, in 2015 the Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organizations (LANGO) was passed, which requires the mandatory registration of all NGOs and Associations, provides the government with arbitrary powers to deny or revoke registration, and places a vaguely worded duty on NGOs and associations to “maintain their neutrality towards political parties”.

The biggest blow to the political opposition has been the amendment last year of the Law on Political Parties (1997), amended twice within four months, which empowers the Supreme Court to dissolve parties, and four election laws, which permits the redistribution of a dissolved party’s seats in the country’s senate, national assembly, and commune and district councils.

Last November, the Supreme Court, presided over by a high-ranking member of the CPP, used the amended Law on Political Parties to dissolve the main opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), which had received just under 44% of the vote – or about 3 million votes – in communal elections held in June 2017.

After the CNRP’s dissolution, the amended election laws were then used to redistribute CNRP seats at every level of government, from the commune to the senate, to the CPP and minor parties.

To silence the media, the country’s media and taxation laws have been invoked – local radio stations have been ordered to stop broadcasting Radio Free Asia and Voice of America “in order to uphold the law on media” and the independent Cambodia Daily was forced to close after being presented with a disputed US $6.3 million tax bill which the Daily claimed was “politically motivated” and not accompanied by a proper audit or good faith negotiations.

To curb the exercise of freedom of expression, the Constitution has received vaguely worded amendments placing an obligation on Cambodian citizens to “primarily uphold the national interest” while prohibiting them from “conducting any activities which either directly or indirectly affect the interests of the Kingdom of Cambodia and of Khmer Citizens”.

Meanwhile individual journalists, members of the political opposition including the CNRP’s leader, Kem Sokha, human rights defenders and an Australian documentary filmmaker have been charged with any number of a kaleidoscope of crimes ranging from intentional violence and criminal defamation to treason and espionage.

And Cambodia lacks an independent and impartial judiciary.

In 2014, three “judicial reform laws” were passed which institutionalized the prosecution and judiciary’s lack of independence from the executive.

At the same time, the government perversely uses the doctrine of the “rule of law” to justify its actions.

Just hours after the Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP, Hun Sen announced that the decision was made “in accordance with the rule of law.”

When members of the diplomatic community and senior UN officials meet government officials to express concern at the increasing misuse of the law they receive an absurdist legal lecture on the “importance of the rule of law”.

What is happening in Cambodia is the opposite of that.

The International Commission of Jurists, UN authorities and others have been defining the rule of law since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was pronounced in 1948.

All agree that that the rule of law entails passing and implementing laws consistent with a country’s international human rights obligations.

It is time for the international community to recognize that a frank and fresh analysis of the situation in Cambodia is urgently required which acknowledges the way the country’s underlying legal and constitutional framework has been deliberately altered, and the way in which this will impact the country adversely long past this month’s election.

This acknowledgment must be accompanied by a coherent and, where possible, joint, plan of action that clearly sets out, with a timeline, what is required to bring Cambodia back on track with the agreed terms of the Paris Peace Agreements – including necessary legal and justice sector reforms – and the political and economic consequences for not doing so.

As long as Hun Sen’s Government deploys increasingly sophisticated justifications for its repressive actions, a more refined, multilayered and vigorous response from the international community is required – grounded on a proper application of the rule of law and Cambodia’s international human rights obligations.

Jun 23, 2017 | News, Op-eds

An opinion editorial by Belisário dos Santos Júnior, a Brazilian lawyer who is a member of ICJ’s Executive Committee.

When assessing the Brazilian political situation, it is important to always mention the date, since the situation changes almost every minute, following the rhythm of denunciations and accusations.

Over the past three years, the main preoccupation of most people living in Latin America has been the level of violence in their countries.

In Brazil, however, although political and criminal violence is high, corruption has been the primary concern of the population, before health and with violence coming in only third position of the population’s concerns (source: Latino barômetro).

The yearly global corruption perception index of Transparency International put Brazil in the 79th position, of 176 countries rated (where 1st position is given to the country with the lowest perception of corruption and 176th given to the country with the highest perception of corruption) with a grade of 40 (0 is for the most corrupted countries and 100 for the cleanest ones).

Brazil was sharing its position with countries such as China, India and Belarus. Its grade was 3 points below the world average.

The report mentioned a clear relationship between corruption and inequalities, creating a vicious circle between corruption, unequal distribution of power and unequal distribution of wealth. How can we correct this?

Brazil is currently reacting to the problem with new laws, new police investigations and legal proceedings, which are important.

But these measures alone will not be enough to change a culture of bypassing laws into a culture of integrity and respect of honesty.

The last elected government, elected in 2014, with Dilma Rousseff as President and Michel Temer as Vice-President (photo), should have lasted until 2018 but fell in 2016 with the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff led by the President of the Federal Supreme Court and decided by the National Congress after two ballots.

Rousseff was accused of having manipulated the federal budget to hide the country’s real economic situation. Michel Temer assumed office as President following Rousseff’s impeachment.

Lula da Silva, the former President (2003-2010), ended his term in the middle of a legal storm when the Federal Supreme Court issued its judgment on the Criminal Lawsuit 470 (corruption of parliamentarians to maintain the influence of the Government in the Congress) and sentenced to prison ministers, businessmen, leaders of Lula’s Workers’ Party and other party leaders.

With the progressive use of the system of delação premiada (which is where a defendant is granted a reduced sentence or other beneficial measure for providing evidence against other persons), a measure included in the new Brazilian law to combat criminal organizations, and a series of police operations (the most famous of which is the operation Lava Jato, or ‘Car Wash’ in English), even more politicians and businessmen have been arrested and/or tried for corruption or money laundering.

More than one third of the National Congress’s members have been targeted by police operations for being implicated in controversial acts, either as agents or beneficiaries.

The current President, Michel Temer, and some of his ministers are under investigation by the Federal Police and on the verge of being denounced by the Federal Prosecutor’s Office for passive corruption.

The last two delação premiada, those of the CEOs of two Brazilian transnational corporations (Odebrecht and JBS), have overturned the political order, and so did the information that more than 2000 politicians received money from slush funds to finance their election campaigns.

Two governors and various parliamentarians are already in jail, including the former President of the Chamber of Deputies, Eduardo Cunha.

Lula da Silva himself is already facing various legal proceedings for corruption.

The winning ticket of the 2014 presidential election was recently judged in a case concerning potential abuse of economic power during their campaign.

Following a very close vote (4 against 3), the Superior Electoral Court rejected claims that illegal money was used in the Rousseff-Temer campaign.

If convicted, Michel Temer would have been forced out of the presidency.

The claim of economic power abuse was rejected only on a procedural matter: the evidence gathered – recordings, pictures, content of delação premiada – was considered inadmissible.

Aécio Neves, the opposition leader who competed against the Rousseff-Temer ticket in 2014, is in no better situation: a few weeks ago, a judicial decision deprived him of his mandate in the Federal Senate.

His sister and his cousin are already in jail and he himself is at risk of being sent to prison if the Federal Supreme Court requests this from the National Congress.

The Brazilian institutions are under investigation, but they are still functioning. Even members of the judiciary and the prosecutor’s office are being investigated.

There is still a decent level of trust in the work the current economic team is doing.

The National Congress gave its approval for the Constitutional Amendment on the Expenditure Ceiling, which will impose a series of conditions to public spending over the next few years. This somehow increases the credibility of the country’s economy.

On the agenda of the Congress, but affected by the series of denunciations for corruption that have hit parliamentarians, are the social security and labour reform bills considered essential for the future of the country by all the economic experts.

But it must also be noted that in the name of the fight against corruption, the Police and Federal Prosecutor’s Office have committed some abuses, to the point that a judge of the Supreme Court said Brazil was on the way to turning into a police state.

Corruption has reached such a level of intensity in the Brazilian political world that people are left in a severe and dangerous state of disappointment and despair. Already the current President is reaching a mere 1% approval rating…

Only elections would improve such a situation. The next presidential election is scheduled in 2018. But who will be eligible to run for it? The law prevents anyone who has a police record from applying.

However, society is reacting, taking various initiatives that value integrity measures, compliance actions, measures linked to education, in addition to the holding of intense debates demanding respect for democracy and human rights and calling for political reform.

Some people want direct elections now but this is contrary to the Constitution. However, 2018 is a long way to go and in the meantime there will be many public demonstrations.

But one thing is sure: Brazil is greater than the crisis it is facing now. This country has survived worse situations, including two long periods of dictatorship. Brazil will battle against this new agony. Respect for democracy, the Constitution and rule of law will prevail at the end.

A versão portuguesa pode ser descarregada abaixo:

Brazil-Corruption crisis-News-Op-ed-2017-POR (em PDF)

May 30, 2017 | News, Op-eds

An opinion piece by Sean Bain, ICJ legal consultant in Myanmar, and Vicky Bowman, Director of the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business.

A strategic environmental assessment is needed to enable sustainable development and the fulfilment of human rights for the people of Kyaukphyu, the site of a planned SEZ and deep-sea port.

In its interim report released in March, the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State chaired by former United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan, called for a comprehensive assessment of the special economic zone in Kyaukphyu Township.

The aim would be to “explore how the SEZ may affect local communities and map how other economic sectors in the state may benefit (or possibly suffer) from the SEZ”.

The State Counsellor’s Office endorsed the commission’s interim recommendations, including for this assessment.

The call for a comprehensive assessment in Kyaukphyu echoes a proposal from our organisations, the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business and the International Commission of Jurists, for the government to undertake a strategic environmental assessment.

Its purpose would be to address concerns about human rights and to consider the cumulative environmental and social impacts of planned developments. Oxfam has put forward a similar recommendation to the government.

Our recommendation comes as media reports this month suggest that the government is giving renewed attention to the future of the SEZ and related projects in Kyaukphyu.

The SEZ, which has been planned to include industrial parks along with deep-sea ports and transport links to China, would transform the demographic and economic character of Rakhine State’s central coast and hinterlands.

It would have significant impacts for local communities and the state economy, both during and beyond the envisaged 20-year construction period.

Kyaukphyu – already the starting point for oil and gas pipelines to China – would host the largest development project ever undertaken in Rakhine State.

Financed mostly by Chinese investors, with shipping facilities linking Myanmar to international routes through the Bay of Bengal, the project also has national and regional economic significance.

However, to date there has been insufficient consideration of the impacts, either positive or negative, on the livelihoods and human rights of residents and the economy of Rakhine State.

Plans for the SEZ are ambitious yet detailed information is scarce and so far there has been no genuine public participation in planning processes.

While contracts and payments regarding investments are decided in Myanmar’s economic and political capitals, it is at the local level that negative impacts can be felt the most.

It is also at the local level where economic benefits may be enhanced.

To address negative impacts and enable benefits, a joined-up approach that brings together national and local government and local and foreign companies with the people of the area is needed.

At present, a lack of coordination across ministries, and between national and regional governments is limiting the scope to harness opportunities and manage impacts of investments.

Despite their significance, neither the SEZ and deep-sea ports nor the offshore gas projects serviced from Kyaukphyu are included in Rakhine State’s socioeconomic development plan.

We believe a strategic environmental assessment is needed to enable sustainable development and the fulfilment of human rights in the Kyaukphyu area.

Strategic environmental assessments, which are part of Myanmar law, are defined in the 2015 Environmental Impact Procedure as “a range of analytical and participatory approaches that aim to integrate environment into policies, plans and programs and evaluate the inter-linkages with economic and social considerations.

The principle is to integrate environment, alongside economic and social concerns, into a holistic sustainability assessment.”

Unlike an environmental impact assessment, which is a permitting requirement for individual projects, a strategic environmental assessment takes a holistic approach by integrating environmental and social concerns and human rights protection, to produce a big picture view of the impacts of interrelated projects.

At Kyaukphyu, the national and state governments – drawing on financial and technical assistance from development and human rights partners – could commission expert independent consultants to undertake the necessary studies and analysis to produce such an assessment.

The assessment would consider the cumulative human rights and environmental impacts of the SEZ, seaports, pipelines, offshore gas developments and transport and energy infrastructure, including impacts on traditional fishing and farming livelihoods in Kyaukphyu.

It could address how best to avoid or minimise the physical and economic displacement of residents, and how to reduce the potential for local tensions and conflict associated with expected socioeconomic transformations.

A legal framework – based on international law and standards – for protecting human rights during economic displacement and resettlement needs to be put in place. That’s not just for the SEZs, but for all projects.

While insufficient to address the lack of legal accountability in the SEZ Law and the limited access to justice in Myanmar, a strategic environmental assessment could improve transparency and give voice to the views of local communities, businesses, civil society organisations and other stakeholders.

This would help fill major gaps in planning and decision-making processes thus far.

Consultation is critical to the value and legitimacy of any assessment but too often it is tokenistic or minimised to cut costs and time.

Development partners should ensure that they are funding genuine and extensive public participation.

A lesson from Myanmar’s only other assessment of this kind, currently underway with support from the International Finance Corporation focused on the hydropower sector, has been the need to communicate and engage constantly about the purpose and process of the assessment.

Many civil society groups chose not to participate in consultations for the IFC-backed assessment due to scepticism and lack of confidence in the process.

To learn from this experience, international and local NGOs in Kyaukphyu could share information and support communities to make informed decisions about their engagement with a strategic environmental assessment.

Until there is a concrete and transparent plan to manage impacts from development projects in Kyaukphyu, particularly those with negative impacts on human rights, current preparations for the SEZ should be put on hold.

This includes land acquisition that is underway and risks violating the rights of local residents.

The government should also delay entering into investment agreements with the winning consortium of developers, which is led by China’s CITIC Group, until there has been broader multi-stakeholder debate about the SEZ, and how it may develop and interact with other investments in the area.

A strategic environmental assessment in Kyaukphyu could contribute towards correcting a development process that has so far not contributed meaningfully to the realisation of human rights or addressed the economic needs of the population in Kyaukphyu or Rakhine State.

We hope that the Myanmar government at national and state level as well as development partners will take this forward, building on the advisory commission’s recommendation and its endorsement by the state counsellor.