A special feature by Juan Velez Rojas

For several decades, Colombia has been a dangerous country for human rights defenders (HRDs) to carry out their critical work. Despite government measures to protect them and the signing of the 2016 Peace Agreement, this situation has not changed and may even be getting worse.

A 2020 report (A/HRC/46/35) of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, Mary Lawlor, pointed out that according to documentation produced by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), between 2015 and 2019, Colombia was the country with the highest number of killings of HRDs in the world.

In that same report, the Special Rapporteur highlighted that, according to the OHCHR, between 2015 and 2019, HRDs had been killed in at least 64 countries. In that period, the OHCHR registered 1,323 killings of HRDs, of which 933 (70.52%) were committed in the Latin American and Caribbean region. In Colombia, 397 killings were committed, that is, 30 per cent of the total of known and recorded HRDs worldwide.

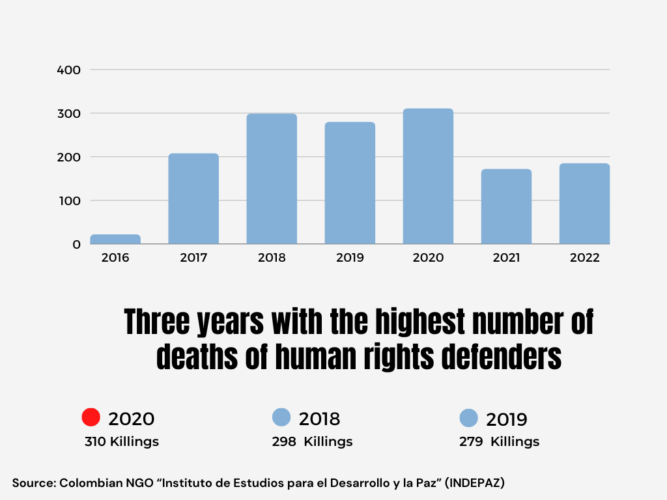

Data from the Colombian NGO Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (INDEPAZ) point to appalling circumstances in the situation of HRDs in Colombia since the signing of the 2016 Peace Agreement between the Colombian Government and the then Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia –People’s Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia guerrilla – Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP). According to the documentation carried out by INDEPAZ, from 24 November 2016 to 23 November 2021, 1,270 HRDS, including social leaders, such as representatives of peasants and indigenous groups, were killed in Colombia.

These figures demonstrate a significant increase in the number of killings of human rights defenders. For example, according to the Colombian humanitarian organization Somos Defensores, during the seven years prior to the signing of the Peace Agreement (2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016) 426 human rights defenders were killed.

INDEPAZ data also indicates that in 2022, 189 HRDs were killed, the fourth year with the highest number of killings of HRDs in Colombia since the signing of the Peace Agreement.

Several civil society organizations have linked the vacuum left by FARC-EP and the illicit activities of various illegal criminal armed groups, including armed attacks to control of territories for coca production, with the increase in the number of killings of HRDs.

The information collected by INDEPAZ reveals that killings in 2022 have occurred in 29 of the 32 departments of the country, but they have been concentrated to the greatest extent in the regions of Cauca (27 killings); Nariño (22 killings), Antioquia (20 killings), Putumayo (18 killings), Valle del Cauca (15 killings) and Arauca (13 killings).

INDEPAZ data shows that community leaders have been the most targeted. Of some 189 killings committed in 2022, 61 victims belonged to this type of social leadership; followed by members of indigenous groups, with 45 deaths; civic leaders (31), peasants (12), and persons of African descent (12).

This data seem to reveal the escalation of armed conflict in various regions of the country. In this regard, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) denounced, in a 2021 report, the existence of six internal armed conflicts in Colombia.

Despite the existence of laws and various mechanisms to protect HRDs, established by the different Colombian governments since 2016 (Juan Manuel Santos, Iván Duque, and Gustavo Petro), a number of international organizations and experts have stressed that these are either ineffective or have not been implemented.

To better understand this situation, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) spoke with Yurley Alejandra Gallo, a human rights lawyer working for the Colombian civil society organization dhColombia. Gallo criticized the work of the National Protection Unit (Unidad Nacional de Protección, UNP), a government institution in charge of protecting people who receive threats against their life or personal integrity, including human rights defenders. In particular, she pointed out that the UNP had not managed to carry out the strategies to effectively protect human rights defenders, including prevention of risks, strategies to counteract threats and minimize vulnerabilities”.

Human rights lawyer, Jeimi Aguilera, was also critical of the efforts by Colombian authorities. In particular, she highlighted that the Colombian authorities had failed to consider that the killings, harassment, and threats against HRDs were systematic in nature. Aguilera also pointed out that it was problematic that some authorities addressed human rights violations against HRDs as crimes linked to their private and personal lives. In other words, authorities had erroneously considered that the attacks or aggression come from the HRDs’ private sphere and not from their work in connection with the defense of human rights.

Óscar Montero, an indigenous leader of the Kankuamo people, from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and an advocate of the rights of indigenous peoples, told the ICJ that society and the government must continue to insist on implementing programs that truly guarantee the lives of the indigenous peoples of Colombia and HRDs.

“Although we have a series of decrees, laws, regulations, and declarations in the country, actually, it must be said, we are in a country where the law is created, but it is not implemented and the rights of indigenous peoples and their advocates in Colombia are not guaranteed. We can say that there have been, on paper, a lot of regulations, but when they are implemented, when they are developed and made effective, they fall short of the dimension and situation of violence that exists in the country”, Montero said to the ICJ.

“We have no protection of our lives. There is a unit, the National Protection Unit, and it does not have a distinctive approach to addressing the indigenous territories and communities in the country considering the individual, collective and territorial needs,” Montero affirmed.

What do the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights say?

Both the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) have pointed out the absence of effective control by the State over various regions of the country, especially areas that were previously under the control of the extinct FARC-EP.

In 2021, the IACHR found that in Colombia, violence was concentrated in territories of the Pacific region and in the Antioquia department. These are territories, which, according to the IACHR, are characterized “by a limited presence of the State, where illegal armed groups compete for dominance and control of the different illegal economies (drug trafficking, illegal mining, land grabbing, among others)”.

For its part, the OHCHR, in a report on the human rights situation in Colombia during 2021, highlighted that the killings of HRDs, leaders, and social leaders, verified in the last two years, were perpetrated by members of non-State armed groups and criminal organizations.

The OHCHR found that “the majority of the victims were defenders of land and territory, the environment, the rights of indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples, peasant communities, as well as people who defended the programs created by the Agreements on Peace, such as the PDET (Development Program with a Territorial Focus) and the PNIS (National Comprehensive Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops)”.

Additionally, according to the OHCHR, the killings of community leaders has been one of the most prominent patterns of extrajudicial killings of HRDs. A pattern occurs due to the search for territorial control by non-State armed actors to engage in illicit economic activities, the control of corridors for drug trafficking, and the illegal appropriation of the most profitable economic activities, and extractive projects.

“These killings weaken the organizational structures of the affected communities and their ability to resist violence, exploitation, and the dispossession of their territory by armed actors. These killings weaken the organizational structures and the social fabric of the affected communities”, highlighted the OHCHR in the report.

According to the same OHCHR document, as a consequence of the threats, the HRDs, to a large extent, stopped their activism, lowered their profile, desisted from their positions and responsibilities as community leaders, abandoned their communities. Some of them left the country.

The seriousness of the current scenario makes it imperative that the Colombian State adopt corrective measures to ensure the effective and timely implementation of the existing measures for the protection of the life and personal integrity of HRDs in Colombia.

In particular, it is important to ensure the effective functioning of a number of protection strategies. These include, in particular, the protection measures granted by the UNP such as the use of escorts, risk analysts and armored cars, as well as communication channels involving the use of a toll-free line and a channel via email to denounce threats and request protection. They also include the strengthening of inter-institutional responses, a strategy for the “de-stigmatization” of human rights defenders, and the strengthening of the processes of investigation, prosecution and sanction of crimes committed against HRDs.

Regarding the situation of HRDs in Colombia and the commitments made by the new government of President Gustavo Petro, Oscar Montero hopes that the promises will materialize and that all protection measures will be implemented: individual, collective and territorial. He also expects that dialogue processes advance and that the physical and cultural attacks against the indigenous peoples in Colombia are brought to an end.

Lastly, Montero reflected on the role that Colombian society has and what it should and can do to accompany HRDs’ work reiterated that “it is very important that Colombian society can continue to accompany and defend its HRDs because in many situations and in parts of the country we are that voice of those communities that do not dare to continue denouncing, that do not dare to continue saying what is happening to them despite being confined, displaced (…) Even so, when they are killing us, when they are threatening us, we are able to continue denouncing because we believe that we cannot leave the communities and those territories alone where the violence is really encrypted”.