The ICJ sent the following letter to the American President.

December 6, 2001

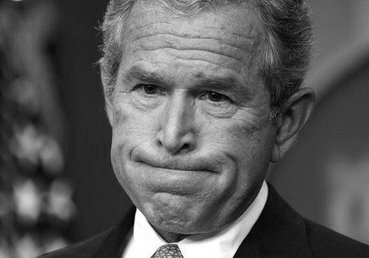

President George Bush

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20500

USA

Fax: 001 202 456 2461

Dear President Bush,

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), which is an international non-governmental organization, consists of judges and lawyers who represent all the regions and legal systems in the world working to uphold the rule of law and the legal protection of human rights.

At a general meeting of all Commissioners and network members, which coincidentally was held during the week of the 11 September terrorist attacks in the United Sates, the ICJ adopted a resolution expressing its horror at the devastating and inhuman terrorist attacks and its heartfelt sympathy for all the tragic victims and their families and to the American people. The ICJ also affirmed its condemnation of all acts of terrorism, which it considered to constitute a vicious violation and subversion of a world order on peace, justice, fundamental human rights and the rule of law. The ICJ urged all governments, all non-governmental organisations and all peoples dedicated to peace, human rights and the rule of law to stand in resolute and committed condemnation of all forms of terrorism.

The ICJ is impressed by the dedication and seriousness of purpose that the United States has brought to bear since the attacks in its effort to combat terrorism. Nonetheless, the ICJ is deeply concerned that certain measures presently being implemented or considered by your government may serve to undermine the very principles that they are aimed at protecting. Particularly troubling is the Executive Order issued by you on 13 November 2001, which authorises the establishment of military commissions to try persons accused of terrorist activities. If implemented, the provisions of this Executive Order may serve to contravene a number of the most fundamental principles relating to the due process and separation of powers. Accordingly, the ICJ would ask that you give serious consideration to rescinding or amending the Executive Order in a manner consistent with the requirements of international law and the United States Constitution.

While the precise rules of procedures of any prospective military Commissions have yet to be announced, the ICJ believes their operation may fail to conform to the minimum standards under both United States and international law for the administration of justice, including the guarantees of liberty and to a fair trial. Among the most problematic features of the tribunals as set forth by the Executive Order are:

- Lack of recognition of the right of detainees to be afforded access to legal counsel

- Lack of recognition of the right for detainees to be informed of charges against them

- Lack of recognition of the right of detainees to be brought before a judicial authority in order to determine the lawfulness of their detention

- No requirement that trials and other proceedings be open and public

- No requirement that judgements or records of proceedings be publicised

- Lack of recognition of the right of accused persons to be provided with the evidence against them

- The accused does not necessarily enjoy the presumption of innocence

- No evidentiary standard, such a “proof beyond a reasonable doubt”, is necessary to secure convictions

- There is no role whatsoever provided for the judiciary in any phase of process

- The only appeal available is to the Executive

- The accused may be convicted by a mere two-thirds majority and may be subjected to the death penalty.

- No notice as to the particular offenses to be covered by the Executive order. (The Order mentions only “acts of international terrorism”, without specifying the particular acts may consist in or in what sources of law they are to be found.)

You have no doubt received a great deal of comment from experts on the possible deficiencies that the Executive Order contains with regard to Constitutional and other domestic law requirements. The ICJ would therefore simply highlight certain of the international law obligations of the United States of which the proposed military commissions may well fall afoul. It is the opinion of the ICJ that each of potential features of the Military Commissions enumerated above may constitute breaches of such obligations.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which the United States is a Party, provides for the right to liberty and security of person, including the right to be free from arbitrary arrest or detention. Under the provisions of article 9, arrested persons must be informed of charges against them, must be brought promptly before a judicial authority, have the right to challenge the lawfulness of their detention, and are entitled to a trial or release within a reasonable time.

As you may be aware, the 1949 Geneva Conventions are among the most well established and widely subscribed to treaties in the international law canon. The United States is a long time party to the Conventions and has long been committed to its principles. Article 3, common to the four 1949 Geneva Conventions, sets forth certain minimum standards, including prohibiting at any time and in any place.

the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by regularly constituted court affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

Article 14 of the ICCR enshrines the right of all persons to a fair and public hearing by a competent and independent and impartial tribunal established by law. The provisions spells out a number of elements of contained in this right, including the presumption of innocence, the right to defense by counsel of one’s own choosing, the right to examine witnesses and equality of arms in the examination of witnesses, and the right to review by a higher tribunal.

It remains unclear as to whether your Government considers itself to be under a state of emergency within the meaning of article 4 of the ICCPR, which would allow for the United States to undertake measures in derogation of some provisions of the ICCPR. Certainly no notification of such a state of emergency has been provided to the United Nations Secretary-General, as required under article 4 (3) of the ICCPR. If the United States were to proclaim a state of emergency, such emergency would have to be of such gravity as to threaten the life of the nation. Any derogating measure undertaken would have to be strictly required by the exigencies of the emergency situation.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee, the body responsible for supervising the implementation of the ICCPR, has commented that: as certain elements of the right to a fair trial are explicitly guaranteed under international humanitarian law during armed conflict, the Committee is of the opinion that the principles of legality and the rule of law require that fundamental requirements of fair trial must be respected during a state of emergency. Only a court of law may try and convict a person for a criminal offence. The presumption of innocence must be respected. In order to protect non-derogable, the right to take proceedings before a court to enable the court to decide without delay on the lawfulness of detention must not be diminished by a State party’s decision to derogate from the Covenant. (CHR General Comment 29.)

The Committee also notes that judicial review of a detention and the right to habeas corpus must remain available even in an emergency situation.

The right to a fair trial no doubt is a guarantee directed to protect individuals charged with a criminal offense. However, it must be stressed that a principal reason that this right has become such a well entrenched principle within the jurisprudence of nations of the world is that without fair trials, the truth of events is unlikely to emerge. Absent the full safeguards afforded to accused individuals, innocent persons are likely to be convicted.

The ICJ is confident that the United States judicial system, among the most highly developed in the world, has the full capacity to conduct fair and effective trials in terrorist cases. Recent prosecutions of terrorists in civilian courts such as in the case of persons charges with the previous bombing of the World Trade Center and attacks on United States embassies in Tanzania and Kenya seem to bear this out. And if certain narrowly circumscribed components of the trial need for legitimate reason to be kept secret, there exist mechanisms through the ordinary judicial channels of the civilian court system that make such a procedure possible.

On a policy level, it seems that the United States would well serve both its own national values and the world community by setting an example in conducting trials in view of the world. Such an undertaking would be important not only to achieve justice in respect of grave crimes, but could also have an educative effect on the international community at large. By keeping most aspects of trials out of the public domain, the United States would be forgoing an opportunity to demonstrate the imperative of human society based on the rule of law, the very destruction of which the terrorists who conducted the 11 September attacks sought to achieve. As some governments and members of the public have expressed suspicions as to the true motives and intentions of your government in confronting terrorism, the convocation of public trials would pose an opportunity to clarify the record and would accord the legitimacy to the process that would no doubt be lacking through the use of military commissions.

In this regard, I would refer your attention to the observations of Mr. Justice Robert Jackson, a member of the US Supreme Court who was the United States Representative to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg during 1945-46. Facing judgment at Nuremberg were the authors of some of the most heinous criminal acts in recorded history. In his letter to President Truman of 7 October 1946, reporting on the outcome of the Nuremberg trials, Mr. Justice Jackson remarked:

In a world torn with hatreds and suspicions where passions are stirred by the “frantic boast and foolish word,” the Four Powers [The United States, Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union] have given the example of submitting their grievances against these men to a dispassionate inquiry on legal evidence. The atmosphere of the Tribunal never failed to make a strong and favorable impression on visitors from all parts of the world because of its calmness and the patience and attentiveness of every Member and Alternates of the tribunal. The nations have given the example of leaving punishment of individuals to the determination of independent judges, guided by principles of law, after hearing all of the evidence for the defense as well as the prosecution. It is not too much to hope that this example of full and fair hearing, and tranquil and discriminating judgment will do something toward strengthening the processes of justice in many countries.

It is with these considerations in mind that the ICJ would ask that you and the members of your administration rethink your position with regard to Military Commissions and ultimately opt to try accused terrorists before your country’s civilian courts.

Yours sincerely,

Louise Doswald-Beck

ICJ Secretary-General

Note: also refer to the Statement regarding the Executive Order issued by President Bush 13. November to Combat Terrorism made by ICJ affiliated organisation, the Norvegian Association of Judges.