May 19, 2021 | News

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) and the Libyan Women’s Platform for Peace (LWPP) on 19 May 2021 convened a webinar on ‘Advancing women’s human rights in the constitutional reform process in Libya’.

The webinar was moderated by Zahra’ Langhi, co-founder and director of LWPP, with speakers: Jaziah Shaitier, Professor at the Criminal Law Department, University of Benghazi; Ibtisam Bahih, member of the Constitution Drafting Assembly; Nahla Haidar, Vice-Chair of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and an ICJ Commissioner from Lebanon; and Azza Maghur, a Libyan lawyer.

In her opening remarks, Zahra’ Langhi stressed that advancing women’s rights in in the constitutional reform process should not be limited to the protections of women’s rights in the draft Constitution, which were any way inadequate, but also the effective the participation of women in the entire constitutional-making process

Jaziah Shaitier focused her remarks on the limitations the Constitution:

“I had hoped that the constitutional process that followed the Revolution would state clearly that any person born to a Libyan father or a Libyan mother would be Libyan.”

“Libya needs gender-inclusive constitutional provisions, and implementing laws that would protect women against all forms of violence”, Shaitier said.

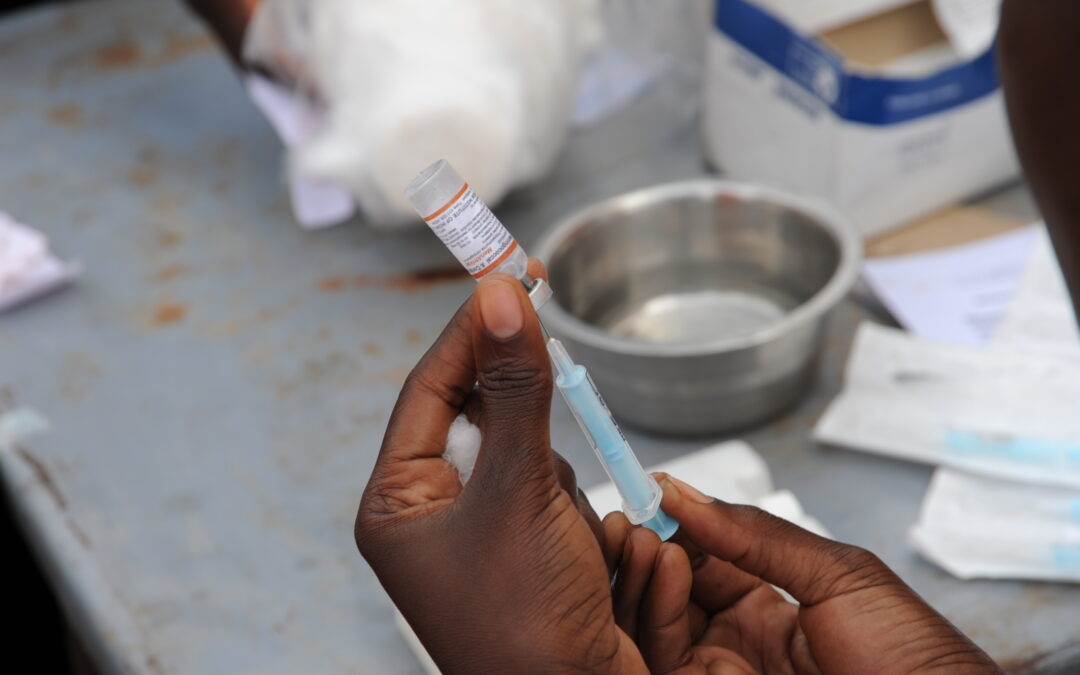

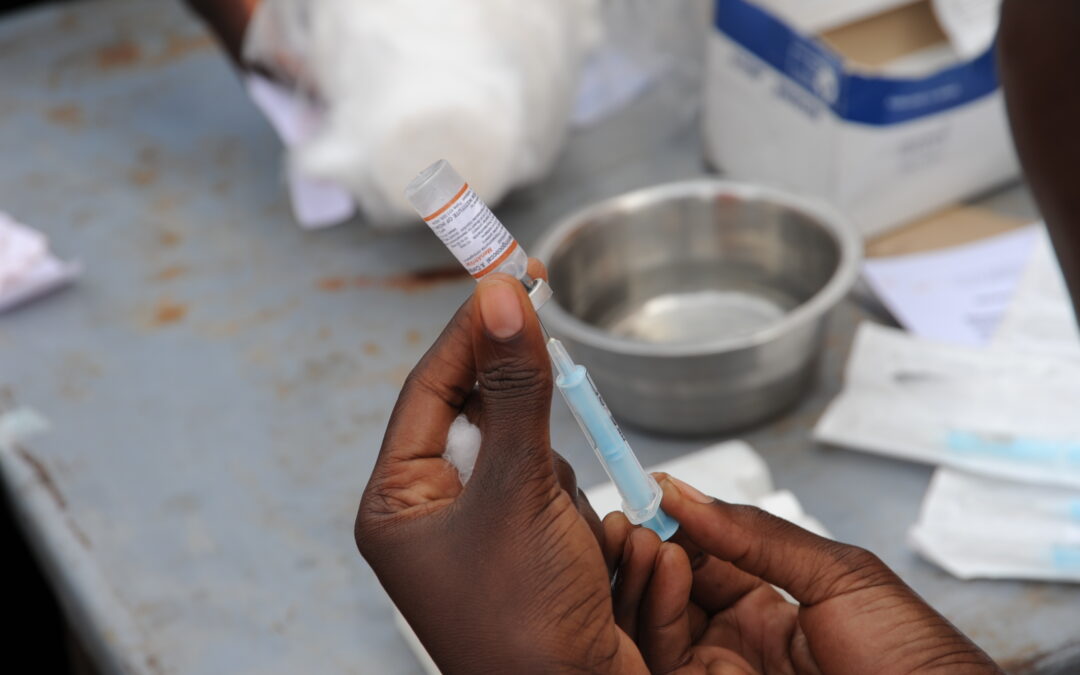

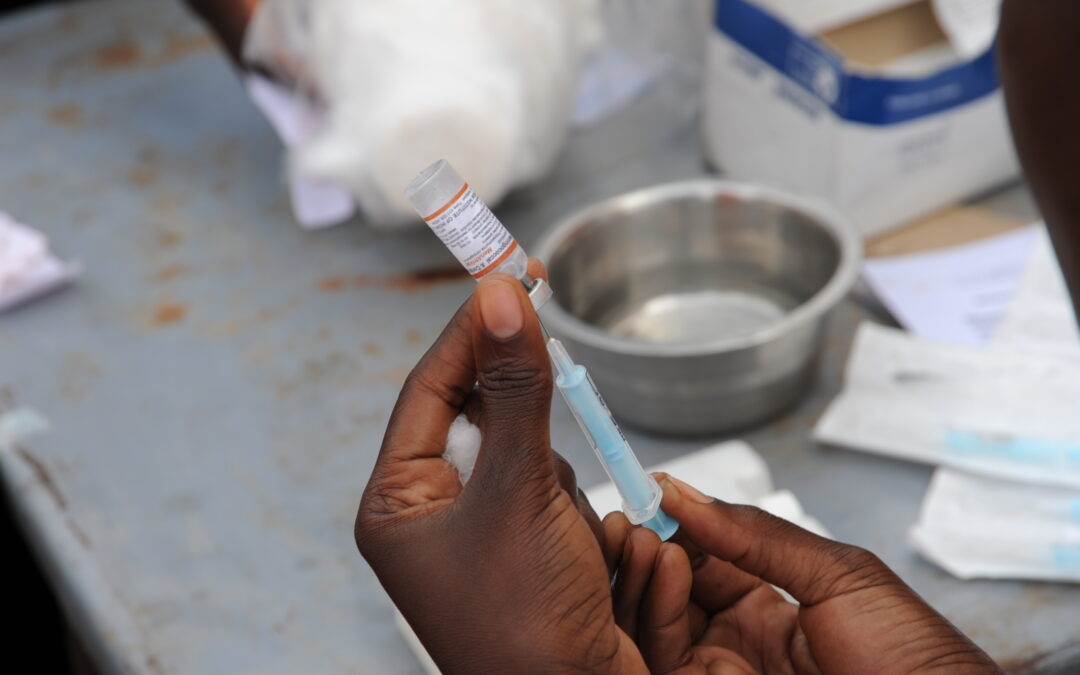

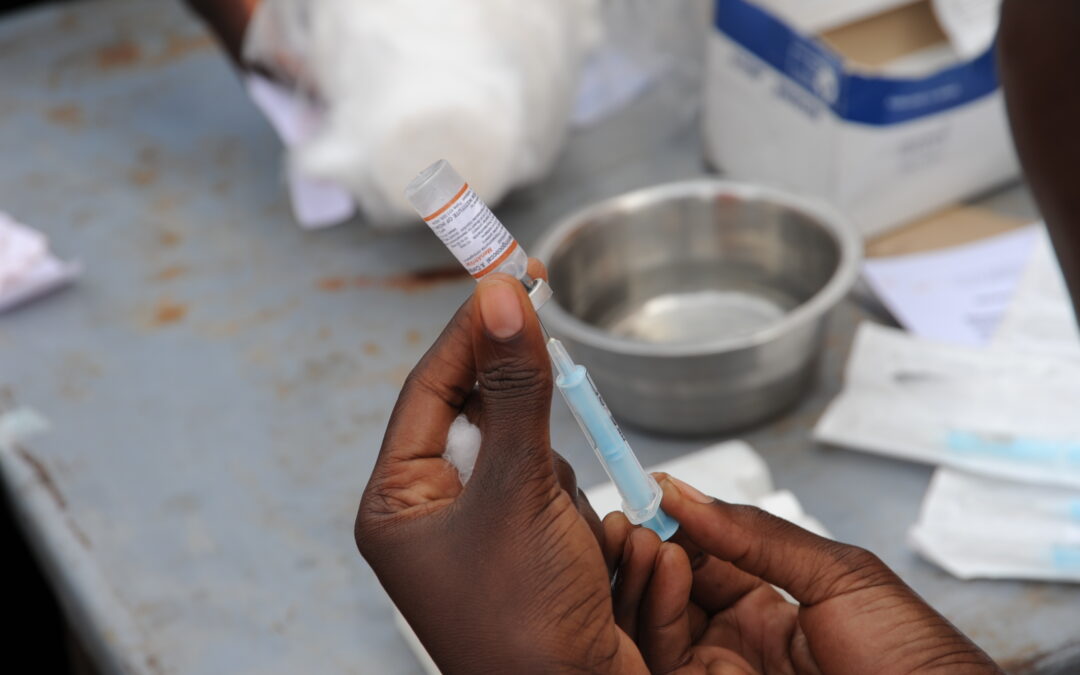

Langhi pointed out that Libyan women who are married to non-Libyans cannot even access essential COVID-19 vaccines.

Nahla Haidar spoke of the importance of states to comply with their obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), a treaty to which Libya is a party:

“Sharia’s place within the Constitution should be made clear, otherwise there would be no need for a Constitution at all.”

Haidar also stressed the need to address problematic provisions in the Libyan Draft Constitution, including draft discriminatory provisions and provisions perpetuating stereotypes about the role of women and men in society and in the family. “Women may also choose not to start a family at all, and that should not have any bearing on the enjoyment of their rights.”

Azza Maghur highlighted the inadequate representation of women in the Libyan constitutional process:

“Libyans dreamed of a Constitution that is theirs, one that guarantees rights and liberties. The representation of women was not adequate.”

A member of the Constitution Drafting Assembly herself, Dr Ibtissam Bahih, highlighted how the process had failed Libyan women, and how the need for reform was as urgent as ever.

You can watch the full webinar here.

Contact:

Said Benarbia, Director, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, t: +41-22-979-3817; e: said.benarbia(a)icj.org

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications Officer, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: asser.khattab(a)icj.org

May 5, 2021 | Agendas, Events, News

On 7 May, the ICJ will hold a public consultation, together with the UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights and Equinet on Access to Justice for Housing Discrimination and Spacial Segregation.

Featured speakers include Special Rapporteur on the right to housing Balakrishnan Rajagopal; retired Justice Zak Yacoob of the South African Constitutional Court; Supreme Court of India Advocate Vrinda Grover; and Equinet human rights defender Valérie Fontaine

More info here.

Mar 29, 2021 | Editorial, Incidencia, Noticias

Por Tim Fish Hodgson (Asesor Legal en derechos económicos, sociales y culturales de la Comisión Internacional de Juristas) y Rossella De Falco (Oficial de Programa sobre el derecho a la salud de la Iniciativa Global para los Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales).

Históricamente, las pandemias han sido catalizadoras importantes de cambio social. En palabras del historiador sobre pandemias, Frank Snowden, “las pandemias son una categoría de enfermedad que parecen sostener un espejo en el que se puede ver quiénes somos los seres humanos en realidad”. Por el momento, mirarse en ese espejo sigue siendo una experiencia lamentablemente desagradable.

Los órganos de los tratados y los procedimientos especiales de las Naciones Unidas, la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS), el Programa Conjunto de las Naciones Unidas sobre el VIH/Sida (ONUSIDA) y numerosas organizaciones locales, regionales e internacionales de derechos humanos han producido múltiples declaraciones, resoluciones e informes que lamentan los impactos de la COVID-19 en los derechos humanos, en casi todos los aspectos de la vida, para casi todas las personas del mundo. El último documento relevante que se ha expedido sobre este tema es una resolución adoptada por el Consejo de Derechos Humanos. Esta resolución hace referencia a “Asegurar el acceso equitativo, asequible, oportuno y universal de todos los países a las vacunas para hacer frente a la pandemia de enfermedad por coronavirus (COVID-19)”. La resolución fue adoptada el 23 de marzo de 2021.

Entre las normas y estándares de derechos humanos que guían los análisis sobre los efectos de la COVID-19, se debe resaltar el derecho de toda persona al disfrute del más alto nivel posible de salud física y mental. Este derecho se encuentra consagrado en el artículo 12 del Pacto Internacional de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales (PIDESC), que tiene 171 Estados Parte. El derecho a la salud, en los términos que está consagrado en el PIDESC, impone a los Estados la obligación de tomar todas las medidas necesarias para garantizar “la prevención y el tratamiento de las enfermedades epidémicas, endémicas, profesionales y de otra índole”. Adicionalmente, respecto a el acceso a medicinas, el artículo 15 del PIDESC establece el derecho de todas las personas de “gozar de los beneficios del progreso científico y de sus aplicaciones”.

A pesar de estas obligaciones legales, a finales de febrero de 2021, el Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas, António Guterres, se sintió obligado a señalar el surgimiento de “una pandemia de violaciones y abusos a los derechos humanos a raíz de la COVID-19”, que incluye, pero se extiende más allá de las violaciones del derecho a la salud. El impacto de la COVID-19 en los derechos humanos ha, y continúa siendo, omnipresente. La gravedad de la situación ha sido perfectamente capturada en las palabras de la activista trans de Indonesia, Mama Yuli, quien al ser preguntada por una periodista sobre su situación y la de otros afirmó que era “como vivir como personas que mueren lentamente”.

Vacunas para unos pocos, pero ¿qué pasa con la mayoría?

Resulta decepcionante que, en lugar de ser un símbolo de esperanza de la luz al final del túnel de la pandemia, la vacuna de la COVID-19 se ha convertido rápidamente en otra clara ilustración de la pandemia paralela de violaciones y abusos a los derechos humanos, descrita por Guterres. El desastroso estado de la producción y distribución de la vacuna COVID-19 en todo el mundo – incluso dentro de países donde las vacunas ya están disponibles– es ahora a menudo descrito por muchos activistas, incluyendo de manera significativa la campaña de “Vacunas para la Gente” (People’s Vaccine campaign), como “nacionalismo de vacunas” y vacunas de lucro que ha producido un “apartheid de vacunas”.

Lo anterior significa, desde una perspectiva de derechos humanos, que los Estados a menudo han arreglado sus propios asuntos de una manera que es perjudicial para el acceso a las vacunas en otros países. Esto, a pesar de las obligaciones legales extraterritoriales de los Estados de, al menos, evitar acciones que previsiblemente resultarían en el menoscabo de los derechos humanos de las personas por fuera de sus territorios.

Es importante enfatizar que solo han pasado unos cuatro meses desde que comenzaron las primeras campañas de vacunación masiva en diciembre de 2020. Al momento en que este artículo se escribe, se habían vacunado aproximadamente 450 millones de personas en todo el mundo. No obstante, mientras que en muchas naciones africanas, por ejemplo, no han administrado una sola dosis, en América del Norte se han administrado 23 dosis de la vacuna COVID-19 por cada 100 personas. En el caso de Europa, la cifra es 13/100. La cifra disminuye drásticamente en el Sur global con 6.4/100 en América del Sur; 3.8/100 en Asia; 0.7/100 en Oceanía y apenas 0.6/100 en África.

Vacunas, obligaciones estatales y responsabilidades empresariales

La distribución inadecuada y desigual de las vacunas tiene diversas causas.

La primera causa es la naturaleza generalmente disfuncional del sistema de salud en todo el mundo. Lo cual se debe a, lo que el Comité de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales (Comité DESC), en su primera declaración sobre COVID-19 de abril de 2020, describió como “decenios de inversión insuficiente en los servicios de salud pública y otros programas sociales”. Las increíbles desigualdades causadas por la privatización de los servicios, instalaciones y bienes de salud, en ausencia de una regulación suficiente, están bien documentadas, tanto en el Norte Global como en el Sur Global.

La segunda causa son los obstáculos para acceder a la vacuna que han sido creados y mantenidos por los Estados, de manera individual o colectiva, a través de los regímenes de propiedad intelectual. Esto no se debe a la falta de lineamientos o mecanismos legales para garantizar la aplicación flexible de las protecciones de la propiedad intelectual a favor de la protección de la salud pública y la realización del derecho a la salud. Sobre este punto, en particular, hay que mencionar el Acuerdo sobre los Aspectos de los Derechos de Propiedad Intelectual relacionados con el Comercio (Acuerdo ADPIC o, en inglés, TRIPS agreement), un acuerdo legal internacional celebrado por miembros de la Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC) que establece estándares mínimos para la protección de los derechos de propiedad intelectual.

Los Estados están explícitamente autorizados para interpretar las protecciones de los derechos de propiedad intelectual “a la luz del objeto y fin del” Acuerdo ADPIC. Por lo tanto, los Estados conservan el derecho de “conceder licencias obligatorias y la libertad de determinar las bases sobre las cuales se conceden tales licencias” en el contexto específico de emergencias de salud pública. Esta no es la primera vez que una epidemia ha requerido que se realicen acuerdos flexibles para garantizar un acceso rápido, universal, asequible y adecuado a medicamentos y vacunas vitales para salvar vidas.

Es por eso que, la gran mayoría de países y un número abrumador de actores de la sociedad civil han apoyado el requerimiento de Sudáfrica y de India para que la OMC emita una exención temporal (waiver) en la aplicación de los derechos de propiedad intelectual para “los diagnósticos, aspectos terapéuticos y vacunas” de la COVID-19. Este requerimiento ha sido formalmente apoyado por distintos expertos independientes de los procedimientos especiales del Consejo de Derechos Humanos. De igual manera, el 12 de marzo de 2021, a través de una declaración, el requerimiento recibió el respaldo enfático del Comité DESC. Adicionalmente, se debe mencionar que ya existen precedentes en la expedición de exenciones temporales sobre derechos de propiedad intelectual. Por ejemplo, la OMC ha aplicado una excepción temporal hasta 2033, para al menos los países menos desarrollados, que los exceptúa de aplicar las reglas de propiedad intelectual sobre productos farmacéuticos y datos clínicos.

Decepcionantemente, no se había secado la tinta de la declaración del Comité DESC, cuando, ignorando explícitamente todas estas recomendaciones, la excepción temporal fue bloqueada por una coalición de las naciones más ricas, muchas de las cuales ya tienen un acceso sustancial y avanzado a las vacunas. Es importante destacar que las recomendaciones del Comité DESC no se formularon por motivos políticos, sino como una manera de cumplir con la obligación establecida en el PIDESC de que “la producción y distribución de vacunas debe ser organizada y apoyada por la cooperación y la asistencia internacional”.

La reciente resolución del Consejo de Derechos Humanos, que fue liderada por Ecuador y el movimiento de Estados no alineados, brinda alguna esperanza de que se altere el actual curso de colisión hacia el desastre. La resolución, que pide el acceso a las vacunas sea “equitativo, asequible, oportuno y universal para todos los países”, reafirma el acceso a las vacunas como un derecho humano protegido y reconoce abiertamente la “asignación y distribución desigual entre países”.

La resolución procede a llamar a todos los Estados, individual y colectivamente, para que se “eliminen los obstáculos injustificados que restringen la exportación de las vacunas contra la COVID-19” y para que “faciliten el comercio, la adquisición, el acceso y la distribución de las vacunas contra la COVID-19” para todos.

Sin embargo, a pesar de las protestas de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil, que participaron en las deliberaciones sobre la resolución, esta solo reafirma el derecho de los Estados a utilizar las flexibilidades del Acuerdo ADPIC, en lugar de respaldar tales medidas como una buena práctica para cumplir las obligaciones de los Estados en materia de derechos humanos. En ese sentido, la resolución adopta un enfoque tibio, en tal vez, la cuestión más apremiante para garantizar el acceso a las vacunas. Este enfoque sigue los principios del comercio internacional, mientras que, irónicamente, ignora los estándares de derechos humanos, que debería considerar por ser una resolución emanada del Consejo de Derechos humanos. Como consecuencia, el enfoque de la resolución en la cuestión apremiante del Acuerdo ADPIC es inconsistente con la perspectiva de derechos humanos, que si tiene el resto de la resolución. Así las cosas, sorprendentemente, la resolución se queda corta y ni siquiera llega a insistir en que los Estados cumplan con sus obligaciones internacionales de derechos humanos establecidas desde hace mucho tiempo.

La resolución tampoco, inexplicablemente, aborda las responsabilidades corporativas, incluidas las de las empresas farmacéuticas, de respetar el derecho a la salud en términos de los Principios Rectores de las Naciones Unidas sobre Empresas y Derechos Humanos, así como el deber correspondiente de los Estados de proteger el derecho a la salud mediante la adopción de medidas regulatorias adecuadas.

La tercera causa, que se encuentra conecta a todo lo anterior, es el fracaso general de los Estados de cumplir de manera plena y adecuada sus obligaciones en materia de derechos humanos en el contexto de las respuestas que han dado a la pandemia de la COVID-19. La redacción sutil pero importante del ejercicio de las flexibilidades del Acuerdo ADPIC como un “derecho de los Estados”, en vez de una forma óptima de cumplir una obligación, expone que existe una asincronía. Específicamente, la manera en cómo los encargados de la formulación de políticas y los asesores jurídicos de los Estados ven y comprenden los derechos humanos, no se alinea con las obligaciones que tienen los Estados en materia de derechos humanos. Obligaciones que, por lo demás, los Estados han asumido de manera voluntaria al convertirse en parte de tratados como el PIDESC.

Un momento crítico: no tiene que ser de esta manera

Como predijo el perspicaz trabajo de Snowden, la pandemia de la COVID-19 representa un momento crítico en la historia de la humanidad. A los Estados, colectiva e individualmente, se les presenta una oportunidad única para sentar un precedente y comenzar a abordar seriamente las causas fundamentales de la desigualdad y la pobreza que prevalecen en todo el mundo.

Tomar la decisión correcta y adoptar una posición moral sobre la importancia del acceso a las vacunas COVID-19 es tanto práctica y simbólicamente importante para que estos esfuerzos tengan éxito. Las vacunas deben ser aceptadas y reconocidas como un bien mundial de salud pública y derechos humanos. Las empresas privadas tampoco deben obstaculizar el acceso equitativo y no discriminatorio a las vacunas para todas las personas.

Para que esto suceda, se requiere un liderazgo decidido de las instituciones internacionales de derechos humanos como el Consejo de Derechos Humanos, la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas y la OMC. Desafortunadamente, en la actualidad, no se ha hecho lo suficiente y la politiquería y el interés privado continúan prevaleciendo sobre los principios y el bien público. Hasta que esto cambie, muchas personas en todo el mundo seguirán existiendo, “viviendo como personas que mueren lentamente”. No tiene que ser de esta manera.

Mar 23, 2021 | Advocacy, News, Op-eds

[TOC]By Tim Fish Hodgson, Legal Adviser on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights at the International Commission of Jurists and Rossella De Falco, Programme Officer on the Right to Health at Global Initiative on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Historically pandemics have often catalyzed significant social change. As historian of epidemics Frank Snowden puts it: “epidemics are a category of disease that seem to hold up the mirror to human beings as to who we really are”. At the moment gazing in that mirror remains a regrettably unpleasant experience.

United Nations human rights Treaty Body Mechanisms and Special Procedures, the World Health Organization (WHO), UNAIDS and numerous local, regional and international human rights organizations have produced reams of statements, resolutions and reports bemoaning the human right impacts of COVID-19 and almost every single aspect of the lives of almost all people around the world. The latest being the UN Human Rights Council Resolution adopted today by consensus on “Ensuring equitable, affordable, timely and universal access for all countries to vaccines in response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic”.

Key amongst the human rights law and standards underpinning these analyses is the protection of the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which, certainly for the 171 States Parties to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights places an obligation on States to take all necessary measures to ensure “the prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases”, and, in the context of access to medicines the right to “enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications”.

Despite these legal obligations, in late February, the UN Secretary General António Guterres felt compelled to highlight the rise of a “pandemic of human rights abuses in the wake of COVID-19”, including, but extending beyond violations of the right to health. The impact of COVID-19 on human rights has, and continues to be, sufficiently ubiquitous that an Indonesian transwoman activist Mama Yuli perhaps captured it best when telling a journalist that she and others in her position were “living like people who die slowly”.

Vaccines for the few, but what about the many?

Disappointingly, however, instead of a symbol of hope of a light at the end of the Coronavirus tunnel, the COVID-19 vaccine has fast become yet another pronounced illustration of the parallel pandemic of human rights abuses described by Guterres. The disastrous state of COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution throughout the world – and even within particular countries where vaccines are available – is now often described by many activists, including significantly the People’s Vaccine campaign, as “vaccine nationalism” and profiteering which has produced a “vaccine apartheid”.

What this means, in human rights language, is that States have often arranged their own affairs in a way that is detrimental to access to vaccines in other countries in spite of their extraterritorial legal obligations to, at very least, avoid their actions that would foreseeably result in the impairment of the human rights of people outside their own territories.

It is worth emphasizing that it has still been only some four months since the first mass vaccination campaigns began in December 2020. At the time of writing, approximately 450 million people had been vaccinated worldwide, while many African nations, for example, had yet to administer a single dose. While in North America 23 COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered per 100 hundred people, with the number standing at 13/100 in Europe, the ratio decreases dramatically in the Global South with 6.4/100 in South America, 3.8/100 in Asia, 0.7/100 in Oceania and a mere 0.6/100 in Africa.

Vaccines, State Obligations and Corporate Responsibilities

The inadequate and inequitable distribution of vaccines has a variety of causes.

First, is the generally dysfunctional nature of the global health system due to what the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights described in its first statement on COVID-19 as early as April 2020 as “decades of underinvestment in public health services and other social programmes”. The incredible inequities caused by privatization of healthcare services, facilities and goods in the absence of sufficient regulation is well-documented, both in the Global North and the Global South.

Second, are the obstacles to vaccine access created and maintained by States, singly but collectively in the form of intellectual property rights regimes. This is not for a lack of guidance or legal mechanisms to ensure the flexible application of intellectual property protections in favour of the protection of public health and the realization of the right to health. The TRIPS agreement is an international legal agreement concluded by members of the World Trade Organization which sets minimum standards for intellectual property rights protections.

States are specifically permitted to interpret intellectual property rights protections “in the light of the object and purpose of” TRIPS and States therefore retain “the right to grant compulsory licences and the freedom to determine the grounds upon which such licences are granted” in the specific context of public health emergencies. Nor is it the first time that epidemics have necessitated the engagement of flexible arrangements to ensure expeditious, universal, affordable and adequate access to life saving medications and vaccines.

This is why the majority of States and an overwhelming majority of civil society actors have supported South Africa and India’s request that the WTO issue a “waiver” of the application of intellectual property rights for COVID-19 “diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines”. This request has also been formally supported by a number of independent experts of the UN Human Rights Council of UN Special Procedures, and recently received the emphatic endorsement of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. There is already precedent for such TRIPS waivers, with the WTO having already applied a waiver until 2033, for example, for least-developed countries (LDCs), which are exempted from applying intellectual property rules on pharmaceutical products and clinical data.

Disappointingly, however, the ink had barely dried on the issuing of the CESCR’s statement, when, plainly disregarding all of these recommendations, the waiver was blocked by a coalition of wealthier nations, many of whom already have substantial and advanced vaccine access. Importantly, the CESCR’s recommendations were not just made on vague policy grounds, but as the best way to fulfill States’ clear legal obligation in ICESCR that, “production and distribution of vaccines must be organized and supported by international cooperation and assistance”.

The recently adopted Resolution of the UN Human Rights Council, led by Ecuador and States of the Non-Aligned Movement and adopted on 23 March 2021 provides some hope of the alteration of this existing collision course with disaster. The resolution, which calls for “equitable, affordable, timely, and universal access by all countries”, reaffirms vaccine access as a protected human right and openly acknowledges “unequal allocation and distribution among countries”.

The resolution proceeds to call on all States, individually and collectively, to “remove unjustified obstacles restricting exports of COVID-19 vaccines” and to “facilitate the trade, acquisition, access and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines” for all.

However, despite the protestations of civil society organizations involved in deliberations about the resolution, the resolution only restates the right for States to utilize TRIPS flexibilities, as opposed to endorsing such measures as a best practice for realizing State human rights obligations. This tepid approach (which follows principles of international trade while, ironically given the resolution emanates from the Human Rights Council, ignoring human rights standards) to perhaps the pressing issue relating to vaccine access is inconsistent with the Resolution’s otherwise firm grounding of vaccine access in human rights. It therefore remarkably even falls short of insisting that States comply with their own long-established international human rights obligations.

The resolution also inexplicably fails to address corporate responsibilities, including those of pharmaceutical companies, to respect the right to health in terms of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and States’ corresponding duty to protect the right to health through adopting adequate regulatory measures.

Third, and connected to the above, is the general failure of States to fully and adequately centre their human rights obligations in the broader context of COVID-19 responses worldwide. The subtle but important phrasing of the exercise of TRIPS flexibilities as a “right of States” rather than as one of the optimal ways of fulfilling an obligation, exposes the degree to which the attitudes by State policy makers and legal advisors towards and understanding of human rights are out of sync with the obligations that they have willingly assumed by becoming party to treaties like the ICESCR.

A Critical Moment: it does not have to be this way

As Snowden’s insightful work predicted, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a critical moment in human history. States, collectively and individually, are presented with a unique opportunity to set a precedent and begin to seriously address the root causes of inequality and poverty which are prevalent across the world.

Making the right decision and taking a moral stand on the importance of access to COVID-19 vaccines is both practically and symbolically important if these efforts are to succeed. Vaccines must be accepted and acknowledged as global public health goods and human rights. Private companies too should not stand in the way of equitable and non-discriminatory vaccine access for all people.

For this to happen, bold leadership is required from international human rights institutions such as the UN Human Rights Council, the UN General Assembly and the WTO. Unfortunately, at present, not enough has been done and politicking and private interest continue to trump principle and public good. Until this changes, many people around the world will continue to exist, “living like people who are dying slowly”. It does not have to be this way.

Feb 24, 2021

An opinion piece by Roojin Habibi, Benjamin Mason Meier, Tim Fish Hodgson, Saman Zia-Zarifi, Ian Seiderman & Steven J. Hoffman

In the COVID-19 response, leaders around the world have resorted to wartime metaphors to defend the use of emergency health measures . Yet, as the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) has noted, States have seldom taken into account corresponding obligations under international human rights law when formulating their ‘call to arms’ against an elusive new enemy.

In assessing the appropriateness of health measures that limit human rights, human rights defenders, academics, international organizations and, most recently, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus have all looked to the Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogations Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Developed in 1984 through a consensus-building effort among international law experts co-convened by the ICJ, the Siracusa Principles sought to achieve “an effective implementation of the rule of law” during national states of emergency, constraining limitations of human rights in government responses. The Siracusa Principles are aimed at ensuring that emergency response imperatives are taken with human rights protections as an integral component, rather than an obstacle. The Principles have since been incorporated into the corpus of international human rights law, in particular through the jurisprudence of the UN Human Rights Committee. They have come to be widely recognized as the authoritative statement of standards that must guide State actors when they seek to limit or derogate from certain human rights obligations, particularly in times of exception – including those states of emergencies that “threaten the life of the nation.”

Framing global health law to control public health emergencies, the World Health Organization’s International Health Regulations (IHR) have long sought to codify international legal obligations to guide responses to infectious disease threats. The IHR, last revised in 2005 in the aftermath of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak, bind states under global health law to foster international cooperation in the face of public health emergencies of international concern. This WHO instrument, which in general terms must be implemented with “full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedom of persons,” seeks to prevent, detect, and provide a robust public health response to disease outbreaks while minimizing interference with international traffic and trade. Yet, the agreement that is legally binding on 194 states parties has been all but forgotten amid the biggest pandemic in a century, with its legal limitations exposed in this time of dire need.

The lack of certainty regarding the scope, meaning and implementation of international human rights obligations during an unprecedented global health emergency has enabled inappropriate and violative public health responses across nations. As the world’s struggle against the coronavirus stretches on, we must begin to consider how global health law and human rights law can be harmonized – not only to protect human dignity in the face future global health crises, but also to strengthen effective public health responses with justice.

The necessarily multi-sectoral response to COVID-19 reveals the distinctive nature of interpreting human rights limitations in a global health emergency that (1) is an international (compared to a national) phenomenon; (2) endangers not only civil liberties and fundamental freedoms, but a broad range of health-related human rights, including the right to health itself; and (3) challenges governments to assess proportionate public health responses in situations of scientific uncertainty.

Global health emergencies raise the imperative for global solidarity

It has proven challenging to ensure that States comply with international standards for permissible human rights limitations amid an emergency that extends across all nations. As a set of standards that primarily guides State conduct in response to national threats to public welfare and security, the Siracusa Principles do not fully contemplate and provide for today’s lived experience in which an international emergency has infiltrated every continent. Similarly, although the IHR make explicit the international duty to collaborate and assist in addressing global health threats, a lack of textual clarity and general failing among states parties to operationalize this obligation render the provision devoid of meaning.

Global solidarity through international cooperation is both a human rights imperative and a global public health necessity. Breakdowns in the international commitment to hasten the supply of COVID-19 vaccines to all States, however, portend future struggles in achieving unity among nations against a common danger. As a number of UN Human Rights Council experts warned in late 2020, “[t]here is no room for nationalism or profitability in decision-making about access to vaccines, essential tests and treatments, and all other medical goods, services and supplies that are at the heart of the right to the highest attainable standard of health for all.” In the coming decades, the world will inevitably face increasing, intensified, and interconnected planetary health threats, including not only the emergence of new infectious diseases, but also the evolution of highly drug-resistant microbes, environmental degradation, climate change, and biological weapons proliferation. Since no country can face these perils alone, overcoming them will require robust, science-based and enduring international cooperation within the framework of “a social and international order in which rights can be fully realized.”

Global health emergencies call for dedicated focus on health-related rights, including the right to health

Nearly all governments have resorted to physical distancing policies to control the spread of disease. While ostensibly adopted to protect public health, such interventions have rarely been accompanied by social relief programmes, such as income support and debt suspension, that are necessary to avoid collateral damage to economic and social rights, including the rights to health, social security, work, and housing. Instead, responses to the pandemic have largely magnified the fault lines of racial, socioeconomic, disability, gender and age inequalities, intensifying the suffering of those already at greatest risk and falling short of State obligations to ensure that responses to public health emergencies do not have discriminatory impacts. However, neither the Siracusa Principles nor the IHR give sufficient attention to the breadth of health-related human rights imperilled by an emergency response. The Siracusa Principles are expressly addressed to limitations of civil and political rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the IHR never mentions the right to health or economic, social and cultural rights, despite WHO’s constitutional mandate to advance the right to health – including the social determinants of health – being central to global health governance.

More than 30 years ago, the HIV pandemic imparted crucial lessons to the world on the intricate linkages between health and human rights. These lessons reverberate once again in the current crisis, reinforcing the interdependence of all human rights as a foundation for global health. Bearing obligations to realize collective rights to public health in a pandemic response, how should States consider the impact of public health emergency measures on their indivisible obligations to realize economic, social, and cultural rights, including the right to health and its underlying determinants? Given the rapid privatization of basic healthcare services and the interests that pharmaceutical companies hold over global vaccine distribution, what are the responsibilities of private actors in the context of public health emergencies? Global health law and human rights law must converge to account for limitations to economic, social, and cultural rights that underlie public health in the context of global health emergencies, and advance effective legal remedies to ensure accountability for the unjustified violation of all human rights in the public health response.

Global health emergencies challenge proportionality assessments in a moment of scientific uncertainty

Under the Siracusa Principles, public health emergencies allow for measures that restrict human rights only to the extent they are “necessary” – that is, measures responding to “a pressing public or social need,” in pursuit of “a legitimate aim,” and “proportionate to that aim.” Government responses to global health emergencies, however, are strained by high degrees of scientific uncertainty, especially at the outset of emerging disease outbreaks. The IHR, much like the Siracusa Principles, evaluates the proportionality of public health measures by requiring that they be no more restrictive of international traffic and no more invasive or intrusive to persons “than reasonably available alternatives,” but it further calls for their implementation to be based on “scientific principles,” “scientific evidence,” and “advice from the WHO.” However, even the IHR’s explicit consideration of scientific knowledge in the proportionality criteria have failed to guide policy actions in the pandemic response.

Selective travel restrictions, for instance, have become the prima facie response not only to the containment of the original SARS-CoV-2 virus, but also to its more transmissible and possibly more lethal variants – despite the discouragement of targeted travel bans under the explicit language of the IHR, mixed scientific evidence of their effectiveness in the absence of other non-pharmaceutical interventions, and historical lessons on their potential to disincentivize the reporting of future outbreak. Measures justified by public health concerns, of which travel restrictions are but one example, if improperly conceived and implemented, may lend themselves to politicization, ineffective or counterproductive public health impacts, discriminatory use, and human rights violations – fracturing the world and distracting from a united and sustainable response to common threats. Moreover, the scientific uncertainty that is inherent to global health emergencies is likely to challenge our conception of how long de jure or de facto national states of emergency may last, and by extension, how to maintain the rule of law, democratic functioning of societies, and realization of the right to health and health-related rights such as access to food, water and sanitation, housing, social security, education and information under such strained conditions.

To hold governments accountable for their management of prolonged global health emergencies, more nuanced normative guideposts are needed. Building on global appeals for public health responses that are anchored in transparency, meaningful public participation, and the “best available science,” careful consideration must especially be given to bridging understandings of “proportionality” under human rights law and global health law.

Harmonizing Approaches in Human Rights Law and Global Health Law: A Call to Action

The COVID-19 pandemic is a harbinger of the evolving nature of emergencies in the 21st century and beyond. Building on the Siracusa Principles and the IHR, any subsequent restatement of the law must take into account these changing circumstances. The pandemic provides an opportunity to clarify human rights law and develop global health law in step with pressing threats to human dignity and flourishment in the modern era. Processes to update, nuance and supplement the Siracusa Principles and IHR are important to this process – providing an opportunity to harmonize human rights assessments across human rights law and global health law.

Working together across legal regimes, the ICJ and the Global Health Law Consortium are developing a consensus-based restatement of principles, drawn from international legal standards, to ensure the harmonization of public health and human rights imperatives as world leaders reconsider the role of international law in guaranteeing rights-based approaches to the inevitable public health emergencies of the future. While the microbe is natural, public health is the product of human will, and in the words of Camus, “of a vigilance that must never falter.”

The ICJ-GHLC invites readers to submit their thoughts, suggestions and/or feedback on a set of principles for global health emergencies to feedback@globalstrategylab.org

Originally published in OpinioJuris on 24 February 2021 here.