Thailand must act to minimize torture and cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment by passing a draft law before the Senate that would criminalize such violations, international experts and Thai human rights defenders urged at a workshop co-hosted on 24 May in Bangkok by the International Commission of Jurists (“ICJ”), Thailand’s Ministry of Justice and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

Thai officials, academics, international experts and human rights defenders discussed how to improve the criminal justice system in holding perpetrators to account and delivering redress to victims of alleged psychological torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (CIDT/P).

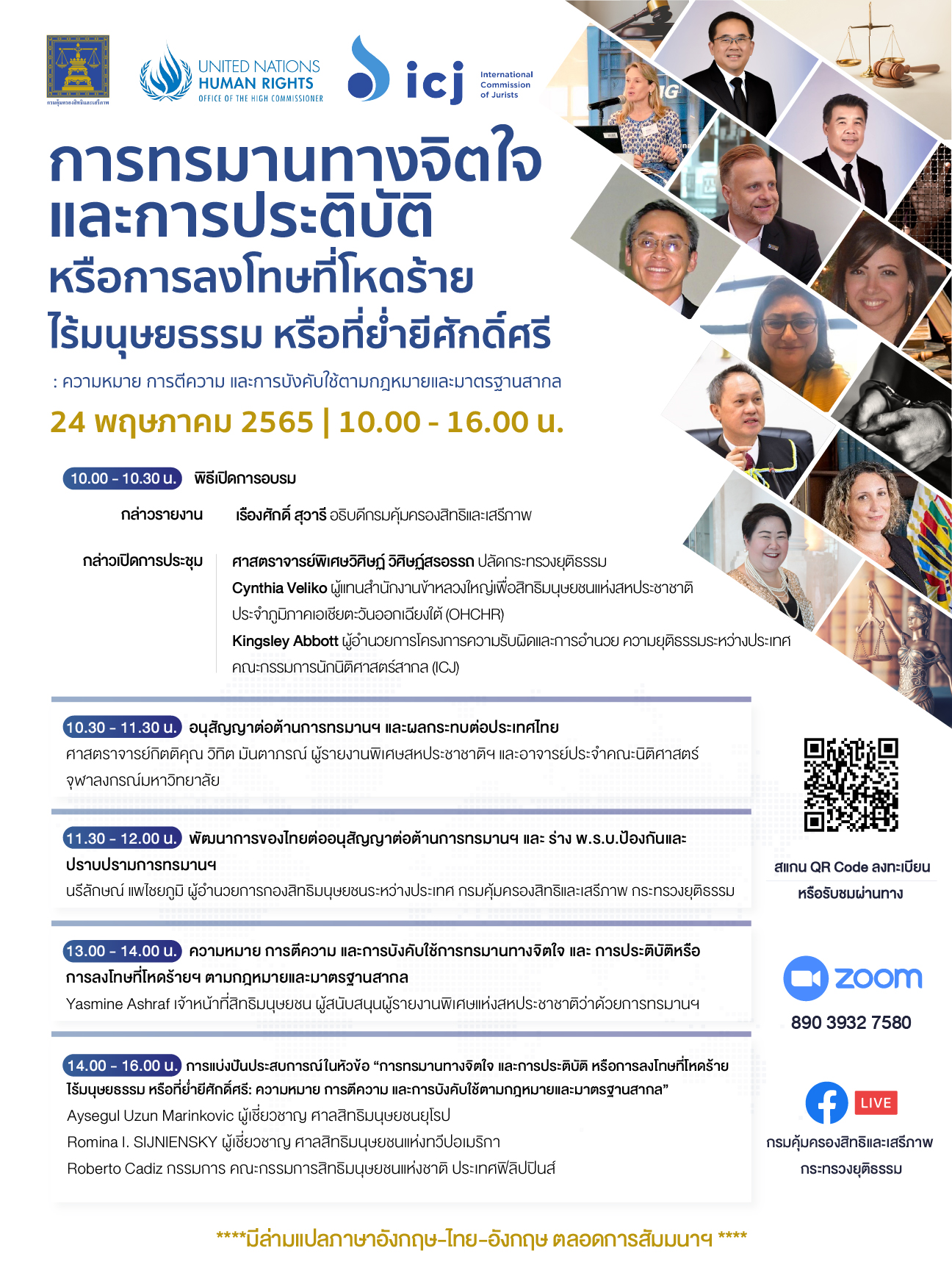

The online Workshop, entitled ‘Psychological Torture and Cruel, Inhumane or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: Definition, Interpretation, and Enforcement in Accordance with International Law and Standards’, was attended by 186 participants, primarily investigators and other justice sector actors. It was also simultaneously live-streamed on the Facebook page of the Ministry of Justice’s Rights and Liberties Protection Department.

Over the past few years, Thai human rights defenders received allegations of human rights violations by security forces and law enforcement officers, including torture and CIDT/P. However, the number of cases in which these allegations have been investigated remains low. Psychological torture and CIDT/P were also often brushed away or trivialized due to the lack of physical marks.

The seminar began with opening remarks delivered by Professor Wisit Wisitsora-at, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Justice of Thailand; Cynthia Veliko, Regional Representative, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Regional Office for South-East Asia; and Kingsley Abbott, ICJ’s Director of the Global Accountability & International Justice.

In his opening speech, Abbott highlighted Thailand’s obligations under international law to ensure that its competent authorities proceed to a prompt and impartial investigation where there is an allegation of torture, not only the one involved significant physical violence, but also “psychological” or “mental” torture and “CIDT/P”.

It was followed by the presentation of Prof Vitit Muntarbhorn, former ICJ Commissioner; and Nareeluc Pairchaiyapoom, Director of International Human Rights Division, Rights and Liberties Protection Department, Ministry of Justice. Both provided an overview of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, its implications for Thailand, and the progress made in enacting the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Act (‘Draft Act’).

In February 2022, Thai lawmakers in the House of Representatives passed the Draft Act. It is going to the Senate for approval. If it passes, the Draft Act will criminalize torture, i.e., the intentional and purposeful infliction of severe pain or suffering “whether physical or mental”, and CIDT/P.

Yasmine Ashraf, Human Rights Officer of the OHCHR with the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on Torture, highlighted that the Special Rapporteurs on torture has consistently found that the effect of torture, regardless of how it has been practiced, is almost always psychological and physical. While it has long recognized “psychological” torture as an analytical concept distinct from physical torture, the mandate holders insist on identical legal consequences and obligations.

Ashraf cited the essential elements of psychological torture, as laid out by the former Special Rapporteur on Torture in 2020, including mental pain or suffering, notably severity, intentionality, purposefulness, and the victim’s powerlessness.

She further clarified the distinction between psychological torture and what is called “no mark torture”, as the latter uses the physical body as a conduit of pain or suffering, using techniques that do not leave visible scars, such as stress positions, sleep deprivation, suffocation, hooding or blindfolding, and long-term exposure to physical discomfort, mental pressure and sensory destabilization. Adversely, psychological torture is intended to target the mind of an individual.

Ashraf’s presentation was followed by the presentations made by experts from other countries, who shared their regional and national laws, case-law, essential elements of torture and CIDT/P, and types of prohibited treatment or punishment relevant to psychological torture and CIDT/P in their respective jurisdictions.

These include Aysegul Uzun Marinkovic, Senior Legal Adviser, Directorate of the Jurisconsult, European Court of Human Rights; Romina I. Sijniensky, Deputy Registrar, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights; and Commissioner Roberto Cadiz, Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines.

Background

Thailand acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in 1996 and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) in 2007. In 2012, Thailand signed the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance but had not yet ratified it.

In an attempt to uncover methods of psychological torture, seven sub-categories of predominant forms of psychological torture were defined by the former Special Rapporteur on Torture in 2020, including methods: (i) targeting the human need for security; (ii) depriving persons from their right to self-determination; (iii) targeting human dignity, feelings of self-worth and identity; (iv) depriving persons from sensory stimuli and environmental control; (v) depriving persons from social and emotional rapport; (vi) depriving persons from the need to communal trust; and (vii) imposing persons to various stressors.

The recording of the workshop is available here.

The report of the Special Rapporteur, examining conceptual, definitional and interpretative questions arising about the notion of “psychological torture” under human rights law, is available here in English and Thai.