An opinion piece by Shaazia Ebrahim, ICJ Media Officer, and Tim Fish Hodgson, ICJ Legal Adviser on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, based in South Africa.

The inhumane conditions that most South African residents are subjected to in their daily lives will continue to deepen as the coronavirus spreads.

South Africans are encouraged to take precautionary measures to curb the spread of the pandemic by practising social distancing and intensifying hygiene control. The country will also be under a nationwide lockdown in order to “fundamentally disrupt the chain of transmission across society” from 26 March for 21 days.

The problem is that the recommended measures in South Africa, similarly to those of the World Health Organisation, assume that everyone lives in a house. A house which is at no risk of being destroyed by the state or private owners of the land upon which it is built: a house with access to water, sanitation and other basic services.

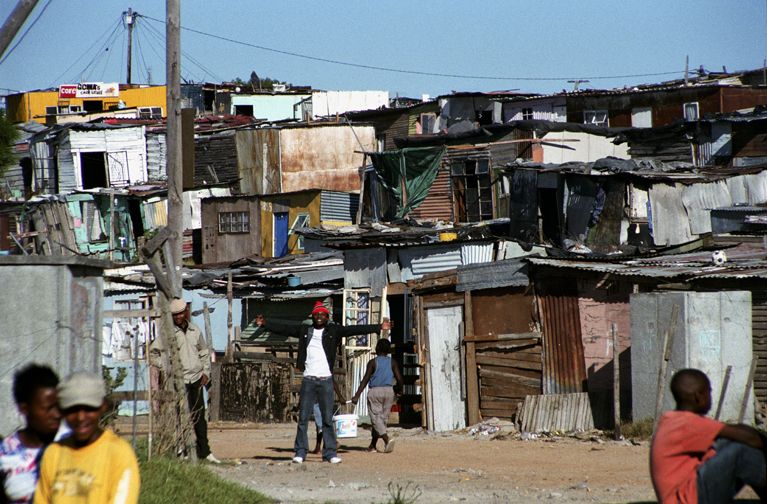

But the reality is that millions of South Africans do not live in a house, but in rudimentary structures in poor conditions. In a statement released this week, Abahlali baseMjondolo, a shack dwellers’ movement with members in various provinces across South Africa, articulated this.

Abahali’s frank assessment of the situation is that “it does not seem possible to prevent this virus from spreading when we still live in the mud like pigs”.

It is under the same conditions described by Abahlali baseMjondolo that many of the urban and rural poor in South Africa will be required to live under “lockdown”, commencing from midnight tonight.

Access to basic services: ‘if one person gets infected it’s disastrous’

Speaking before the release of the statement, Abahlali president S’bu Zikode expressed the distress that many around South Africa are currently experiencing. “Abahlali is very concerned about the outbreak of the coronavirus. The reason is, of course, that the conditions that we are subjected [give] us reason to be scared and worried,” he said.

“Social distancing” is difficult for many in South Africa. Government regulations say no more than 100 people should be “gathering” and people are more generally encouraged to keep a distance from one another. In Abahlali’s settlements, Zikode explains, there are thousands living close together under strenuous conditions.

“That on its own is automatically disrespecting the call from the president”, he said.

Abahlali, alongside various other South African movements and organisations, have for years been calling for the state to improve their living conditions and provide them with access to water, sanitation and other basic services.

In 2019 the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights noted its concern about “the large number of people living in inadequate housing, including those in informal settlements, without access to basic services; the growing number of informal settlements in urban areas due to rapid urbanisation”.

These calls have not received a sufficiently serious response from the government. Litigation to ensure access to basic services remains commonplace.

In this context, while hygiene has rightly been touted as one of the most important preventatives from spreading Covid-19, it is difficult to imagine how the majority living in South Africa will be able to ensure even basic measures such as handwashing.

Abahlali notes that in many informal settlements “hundreds of people [are] sharing one tap”. In this context, it is easy to see why leaders of Abahlali think that as it stands, preventing the spread of coronavirus is very important, but all but impossible.

“As leaders of Abahlali, we see it as once one person gets infected in the settlements, suddenly the entire settlement will be disastrous,” Zikode said.

A moratorium on evictions: halting evictions ‘will save lives’

Making matters worse, members of Abahlali, like many others in their country, lack security of tenure. As trying as their current circumstances may be, Abahlali warns of the potentially devastating effects of evictions during the pandemic. Another common way to induce evictions is to disconnect existing access to water, electricity and sanitation.

This is why Abahlali demands that “all evictions must be stopped with immediate effect” and that “all disconnections from self-organised access to water, electricity and sanitation must be stopped with immediate effect”. Indeed, it is difficult to see how any eviction during the pandemic could be “just and equitable” in “all relevant circumstances” as is required by South African law.

The call for a “moratorium” on evictions has also been made by a large group of social movements and civil society organisations in South Africa in a letter to the president. It has also received clear support from the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, who has called for a “global ban” on evictions worldwide:

“The logical extension of a logical stay-at-home policy is a global ban on evictions. There must be no evictions of anyone, anywhere, for any reason. Simply put: a global ban on evictions will save lives”, she said. The International Commission of Jurists has echoed these calls and the calls for connection of emergency water for all before the nationwide lockdown commences.

Coronavirus, the right to housing and access to land

In February, in giving input to the parliamentary committee contemplating the need to amend the Constitution to expedite land reform, Abahali argued that land is not a commodity and that the Constitution should include a “right to land” which it does not at present.

“Land should be shared and should be viewed as a public good”, Zikode explains.

Abahlali argues that the absence of a right to land in the Constitution undermines the constitutional right to housing: without land there can be no housing. Consistently with this logic, as early as 2000, South Africa’s Constitutional Court held emphatically that:

“For a person to have access to adequate housing all of these conditions need to be met: there must be land, there must be services, there must be a dwelling.”

The current crisis brought on by the coronavirus adds weight to Abahlali’s position on land. Access to land and security of tenure are necessary for access to adequate housing. If people have access to land and secure tenure, evictions are not a constant threat to their well-being.

Without access to housing and basic services, public health is severely compromised on a daily basis. Public health emergencies such as the coronavirus pandemic put even further pressure on an already compromised living environment. They therefore highlight that for many people, the right to adequate housing can only be discharged with full access to land.

The obligations of the South African government

The government of South Africa has rightly been praised for its proactive response to the coronavirus pandemic. The regulations passed in terms of the Disaster Management Act require that measures taken to combat coronavirus are implemented “as far as possible, without affecting service delivery in relation to the realisation of the rights” including the rights to housing and basic services, healthcare, social security and education.

The president’s announcement of a countrywide lockdown included a commitment that “temporary shelters that meet the necessary hygiene standards will be identified for homeless people”. Nevertheless, Abahlali’s members, who are not strictly homeless, might take cold comfort.

Disappointingly, the president failed to announce a moratorium on evictions or make any mention of evictions at all. This not only leaves many more people under the threat of being rendered homeless but may also lead to devastating displacement that will make the further spread of coronavirus possible.

The president did indicate that “emergency water supplies” are “being provided to informal settlements and rural areas”.

However, he did not make mention of whether expedited or emergency provision of other basic services such as sanitation, electricity and waste removal services where they are not currently available would occur. Urgent calls for emergency water connection coming out of Khayelitsha suggest that in many places in major informal settlements such emergency connections have not occurred.

The government of South Africa should be applauded for taking emergency measures. However, in so doing, it is implicitly acknowledging that many — if not most — South African residents have been living on a daily basis in conditions that are insufficient for them to live healthy, dignified lives.

This highlights the government’s existing and continuous failures to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights to access to housing and basic services.

The coronavirus, therefore, stands a stark reminder to all in South Africa of the dire impacts of social inequality in the country and the pressing need for government to pursue the realisation of all its obligations in terms of social and economic rights protected in the South African Constitution and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It also lends strong credence to the need for serious consideration of Abahlali’s claim for the need of a constitutionally protected right to land.

As Zikode concludes:

“Abahlali has always been about the land, decent housing, and dignity. Without land, housing is impossible. Without land, dignity is compromised. Land is close to the heart of many mainly black South Africans and it’s very close to the heart of Abahlali.”

Originally published in Daily Maverick